Top Articles

Kings set to face Oilers in round one of Stanley Cup Playoffs: preview

Fyre Festival 2 stops ticket sales for Mexico event

US News

See all »‘The most powerful type of liar’: Tapper asks Anna Delvey how she views her criminal past

Tornadoes, heavy rains rip across central, southern US

Man faces charges after Teslas set on fire with Molotov cocktails

Wisconsin and Florida elections provide early warning signs to Trump and Republicans

World News

See all »Israel to seize parts of Gaza as military operation expands

Middle East latest: Israel is establishing a new military corridor across Gaza

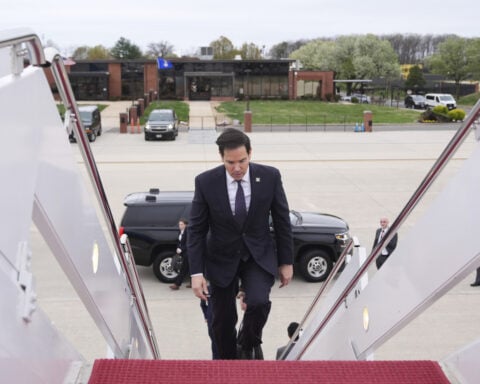

A wary Europe awaits Rubio with NATO's future on the line

China’s military launches live-fire exercise in escalation of blockade drills near Taiwan

Latest

See the moment Vatican announces death of Pope Francis

Former CDC official reveals why he left after RFK Jr. took over

CNN's Anderson Cooper speaks with former CDC communications director Kevin Griffis about his decision to step down after President Donald Trump's pick to lead the agency, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., took over.

Trump said he didn’t sign controversial proclamation. The Federal Register shows one with his signature

President Donald Trump downplayed his involvement in invoking the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to deport Venezuelan migrants, saying for the first time that he hadn’t signed the proclamation, but that he stood by his administration’s move. The proclamation invoking the Alien Enemies Act appears in the Federal Register with Trump’s signature at the bottom. CNN’s Kaitlan Collins reports.

Cory Booker’s historic speech energizes a discouraged Democratic base

Trump's tariffs roil company plans, threatening exports and investment

Businesses around the globe on Thursday faced up to a future of higher prices, trade turmoil and reduced

Stock futures plunge as investors digest Trump’s tariffs

Stock futures plunge as investors digest Trump’s tariffs

Hear Trump break down tariffs on various countries

Attorney for father deported in 'error' says this is what's 'new, unique and terrifying' about case

CNN's Erin Burnett speaks with Simon Sandoval-Moshenberg, the attorney for a Maryland father the Trump administration conceded it mistakenly deported to El Salvador “because of an administrative error.”

Federal judge to consider case of Georgetown fellow arrested by ICE

Federal judge to consider case of Georgetown fellow arrested by ICE

Canadian couple cancels tens of thousands in travel to the US

CNN's Natasha Chen spoke to Gary and Carol Cruise who normally spend a small fortune traveling throughout the US every year. Because of remarks by President Donald Trump and the tariff war, they've cancelled nearly everything.

California & Local

See all »Kings set to face Oilers in round one of Stanley Cup Playoffs: preview

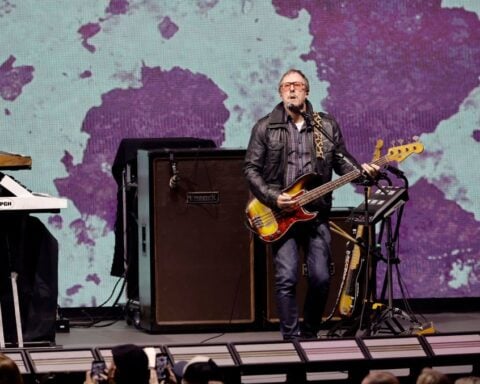

Weezer bassist to play Coachella despite wife’s arrest

Technology

See all »Drones can deliver supplies on Mount Everest this year, and it may change climbing forever

Big Tech's "Magnificent Seven" heads into earnings season reeling from Trump turbulence

South Korea's LG Energy Solution pulls out from Indonesia EV battery investment

Nintendo faces trade war test with Switch 2 launch

Lifestyle

See all »Pope Francis: Key moments from his life

60,000 Americans to lose their rental assistance and risk eviction unless Congress acts

Easter eggs hidden around Boston ahead of the marathon contain a special surprise

Entertainment

See all »Netflix shares rise as rosy outlook calms investors' nerves amid tariff fears

Nintendo faces trade war test with Switch 2 launch

‘Sinners’ finds redemption with top spot at weekend box office

Holly Robinson Peete calls out RFK Jr. on his autism remarks

Trump has begun another trade war. Here's a timeline of how we got here

Trump has begun another trade war. Here's a timeline of how we got here

Canada's leader laments lost friendship with US in town that sheltered stranded Americans after 9/11

Canada's leader laments lost friendship with US in town that sheltered stranded Americans after 9/11

Chinese EV giant BYD's fourth-quarter profit leaps 73%

Chinese EV giant BYD's fourth-quarter profit leaps 73%

You're an American in another land? Prepare to talk about the why and how of Trump 2.0

You're an American in another land? Prepare to talk about the why and how of Trump 2.0

Chalk talk: Star power, top teams and No. 5 seeds headline the women's March Madness Sweet 16

Chalk talk: Star power, top teams and No. 5 seeds headline the women's March Madness Sweet 16

Purdue returns to Sweet 16 with 76-62 win over McNeese in March Madness

Purdue returns to Sweet 16 with 76-62 win over McNeese in March Madness