If you knew Bob Newhart only as an actor – most notably as the star of the legendary “Bob Newhart Show” but also in a minor though memorable role in the movie “Elf” – you may not have thought of him as a literary figure.

However, Newhart, who died on July 18, 2024, at the age of 94, began his rise to stardom as a stand-up comic, crafting and delivering such brilliant monologues as “Driving Instructor” and “Bus Drivers School.” In those bits, he demonstrated a mastery of diction, dialect, character and dialogue worthy of the title “literary master.”

In my view, there is perhaps no more fitting recipient of the Mark Twain Prize than Newhart, who received it in 2002.

As a literary scholar, I typically study traditional poetry and fiction by canonical authors such as Twain and Edgar Allan Poe. But the mastery of language and character is not the sole possession of poets and novelists. Newhart demonstrated that stand-up comedy could also be an art form.

‘The old humble bit’

One of his masterpieces is his “Abe Lincoln vs. Madison Avenue” stand-up routine, built around a quirky but timely premise.

Having witnessed the rise of advertising and public relations in the 1950s and 1960s, Newhart imagined a scenario from an earlier age. What if, he asked, there had been no real man with the mind and stature of Abraham Lincoln during America’s Civil War?

The advertising industry, he goes on to say, “would have had to create a Lincoln.” He then performs a one-sided imaginary telephone conversation between a press agent and someone employed to play the part of this manufactured Lincoln – introducing it with a line that would become iconic for Newhart, saying the conversation would have gone “something like this.”

The “something” that ensues is a tightly crafted, six-minute routine worthy of the term “poem.” Indeed, Newhart deployed some of the same literary devices wielded by previous masters such as Twain and Alexander Pope.

Like Twain, Newhart had a marvelous ear for dialect and seasoned his monologue with little bits of slang and jargon to capture the breezy speech of a stereotypical press agent.

“Hi, Abe, sweetheart, how are you, kid?” he begins. “How’s Gettysburg?”

Delivered quickly and offhandedly, the lines, like so much of Newhart’s stand-up work, are subtle, but effective – dead on without being too on the nose. Throughout the bit, he deploys similar little touches of diction – as when the agent refers to “Four score and seven,” the famous first words of the Gettysburg Address, as a “grabber.”

Herein lies another, even more effective, source of humor. Lincoln’s opening is famously lyrical and formal, the epitome of elocutionary eloquence, and the agent has reduced it to a “grabber.” This kind of deflation echoes an old satirical genre known as the “mock-epic.” As practiced by the Enlightment-era English poet, translator and satirist Alexander Pope and others, it draws its humor from the contrast between the sublime and the mundane or even ridiculous.

Newhart returns to the device when he has the agent try to explain to the made-up Abe the logic behind the line “The world will little note, nor long remember.”

Lincoln’s original line is graceful, alliterative and nearly perfectly iambic – an oratory gem if there ever was one – but, for the agent, it’s simply “the old humble bit.”

Character is key

Master writers of humor or, for that matter, fiction in general, will tell you that character is key. Get the characters right, and humor – or drama – will follow.

With more of his delightfully subtle touches, Newhart paints a hilarious picture of the naive bumbler the agency has to craft into a Lincoln. Again, as is often the case with humor, irony helps to achieve the desired effect – in this case, humor.

Lincoln was an eloquent, noble figure. He was larger than life – and certainly larger than this dimwit, who doesn’t even get the joke when one of the agency’s “gag writers” supposedly dashes off a line on Gen. Ulysses S. Grant.

The agent shares it with the fake Abe, saying, “They got a beautiful squelch on Grant. The next time they bug ya about Grant’s drinkin’ … you tell ’em you’re gonna find out what brand he drinks and send a case of it to all your other generals.”

After a short pause, the agent says, with Newhart’s famous stammer, “Uh, no, no, it’s, it’s like, like the brand, uh, was the reason he won.” Finally, after another short pause, the exasperated agent snaps, “… use it, it’s funny.”

Give the audience credit

This last “exchange” demonstrates the most ingenious aspect of Newhart’s humor: his signature one-sided conversation, which he also used to hilarious effect in “Driving Instructor” and other routines.

Now you know why the opening sequence of “The Bob Newhart Show” has Newhart answering a phone – an homage to his then-famous stand-up gag.

We never hear the voice of “Abe” but rather hear only the agent’s side of the conversation. It might seem like a minor detail, but this artifice means that we as the audience have to play an active role in the comedy. We hear the agent’s side and have to imagine what he is hearing. Sometimes the agent repeats what he supposedly hears, but, in this instance, when the agent is trying to explain the punchline of the Grant joke, the burden is on us.

Here again Newhart was employing an old device. In a dramatic monologue such as Robert Browning’s serious poem “My Last Duchess,” the poet leaves out key details, forcing us to detect them and complete the only partially told story.

The device is especially effective in comedy because, as Newhart knew on some level, we all like to feel smart. By putting us in the position of filling in the blanks in the conversation, Newhart gives us the opportunity to feel a little extra satisfaction and to create some of the humor ourselves by crafting our own sense of the rube on the other side of the conversation.

It was the master stroke for a master craftsman. With this brilliant touch, Newhart turned us all into comedians.

Mark Canada does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Source: The Conversation

Bangladesh Supreme Court acquits ex-Prime Minister Zia, clearing the way for her to run in elections

Bangladesh Supreme Court acquits ex-Prime Minister Zia, clearing the way for her to run in elections

British author Neil Gaiman denies ever engaging in non-consensual sex as more accusers come forward

British author Neil Gaiman denies ever engaging in non-consensual sex as more accusers come forward

A look at the events that led up to the detention of South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol

A look at the events that led up to the detention of South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol

Two private lunar landers head toward the moon in a roundabout journey

Two private lunar landers head toward the moon in a roundabout journey

TikTok preparing for U.S. shut-off on Sunday, The Information reports

TikTok preparing for U.S. shut-off on Sunday, The Information reports

Japan's Makino Milling requests changes to unsolicited bid from Nidec

Japan's Makino Milling requests changes to unsolicited bid from Nidec

As Los Angeles burns, Hollywood's Oscar season turns into a pledge drive

As Los Angeles burns, Hollywood's Oscar season turns into a pledge drive

As fires ravage Los Angeles, Tiger Woods isn't sure what will happen with Riviera tournament

As fires ravage Los Angeles, Tiger Woods isn't sure what will happen with Riviera tournament

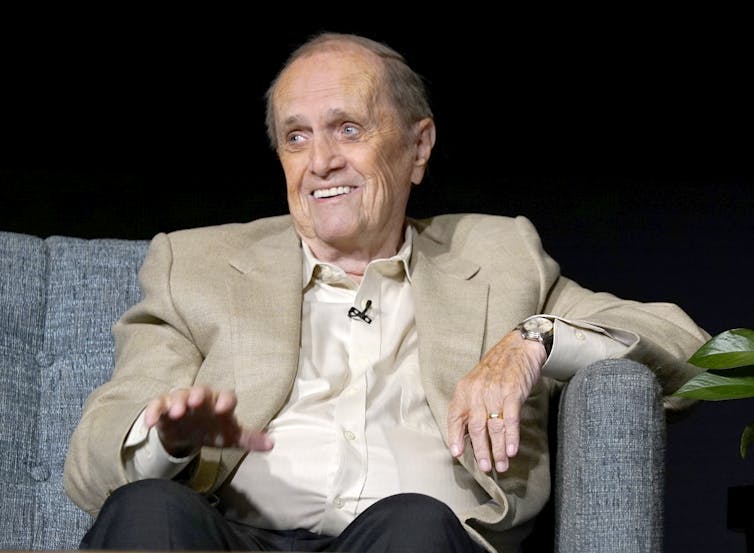

A classic Newhart bit involved making imaginary phone calls, such as in his 'Abe Lincoln' bit.

A classic Newhart bit involved making imaginary phone calls, such as in his 'Abe Lincoln' bit.