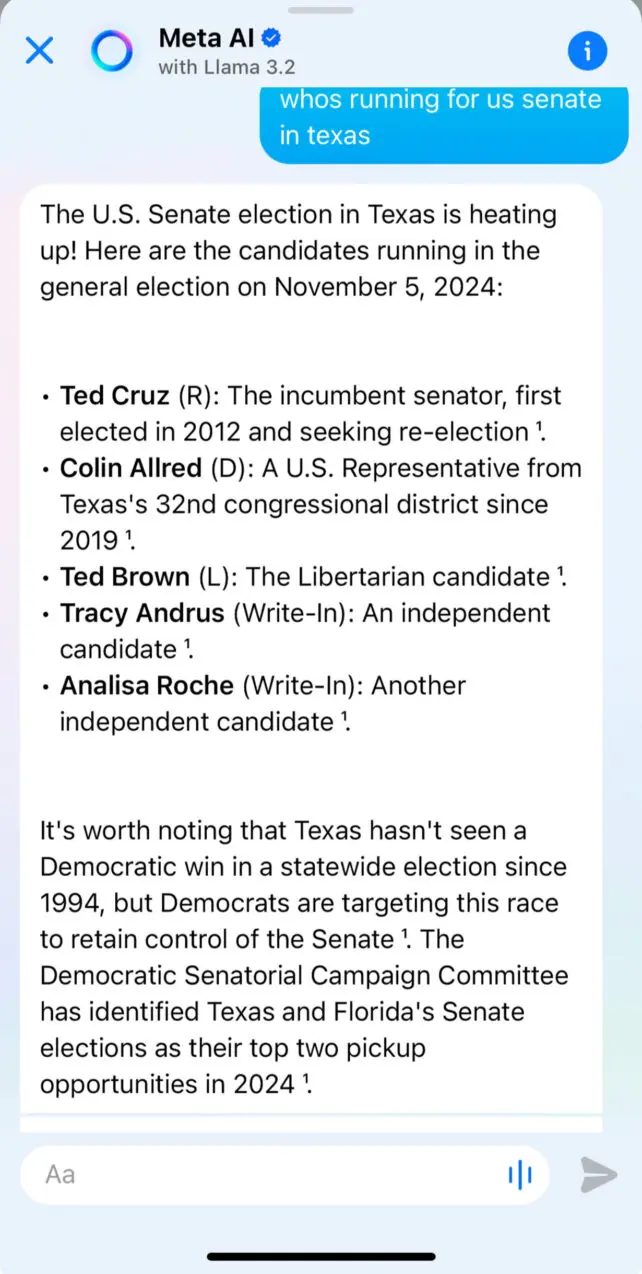

But generative AI can also produce misinformation. In the most extreme cases, AI can have “hallucinations,” offering up wildly inaccurate results.

A CBS news account from June 2024 reported that ChatGPT had given incorrect or incomplete responses to some prompts asking how to vote in battleground states. And ChatGPT didn’t consistently follow the policy of its owner, OpenAI, and refer users to CanIVote.org, a respected site for voting information.

As with the web, people should verify the results of AI searches. And beware: Google’s Gemini now automatically returns answers to Google search queries at the top of every results page. You might inadvertently stumble into AI tools when you think you’re searching the internet.

2. Deepfakes

Deepfakes are fabricated images, audio and video produced by generative AI and designed to replicate reality. Essentially, these are highly convincing versions of what are now called “cheapfakes” – altered images made using basic tools such as Photoshop and video-editing software.

The potential of deepfakes to deceive voters became clear when an AI-generated robocall impersonating Joe Biden before the January 2024 New Hampshire primary advised Democrats to save their votes for November.

After that, the Federal Communication Commission ruled that AI-generated robocalls are subject to the same regulations as all robocalls. They cannot be auto-dialed or delivered to cellphones or landlines without prior consent.

The agency also slapped a US$6 million fine on the consultant who created the fake Biden call – but not for tricking voters. He was fined for transmitting inaccurate caller-ID information.

While synthetic media can be used to spread disinformation, deepfakes are now part of the creative toolbox of political advertisers.

One early deepfake aimed more at persuasion than overt deception was an AI-generated ad from a 2022 mayoral race contest portraying the then-incumbent mayor of Shreveport, Louisiana, as a failing student summoned to the principal’s office.

Blink and you’ll miss the disclaimer that this campaign ad is a deepfake.

The ad included a quick disclaimer that it was a deepfake, a warning not required by the federal government, but it was easy to miss.

Wired magazine’s AI Elections Project, which is tracking uses of AI in the 2024 cycle, shows that deepfakes haven’t overwhelmed the ads voters see. But they have been used by candidates across the political spectrum, up and down the ballot, for many purposes – including deception.

Former President Donald Trump hints at a Democratic deepfake when he questions the crowd size at Vice President Kamala Harris’ campaign events. In lobbing such allegations, Trump is attempting to reap the “liar’s dividend” – the opportunity to plant the idea that truthful content is fake.

Discrediting a political opponent this way is nothing new. Trump has been claiming that the truth is really just “fake news” since at least the “birther” conspiracy of 2008, when he helped to spread rumors that presidential candidate Barack Obama’s birth certificate was fake.

3. Strategic distraction

Some are concerned that AI might be used by election deniers in this cycle to distract election administrators by burying them in frivolous public records requests.

For example, the group True the Vote has lodged hundreds of thousands of voter challenges over the past decade working with just volunteers and a web-based app. Imagine its reach if armed with AI to automate their work.

Such widespread, rapid-fire challenges to the voter rolls could divert election administrators from other critical tasks, disenfranchise legitimate voters and disrupt the election.

As of now, there’s no evidence that this is happening.

4. Foreign election interference

Confirmed Russian interference in the 2016 election underscored that the threat of foreign meddling in U.S. politics, whether by Russia or another country invested in discrediting Western democracy, remains a pressing concern.

Special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into the 2016 U.S. election concluded that Russia had worked to get President Donald Trump elected.

In July, the Department of Justice seized two domain names and searched close to 1,000 accounts that Russian actors had used for what it called a “social media bot farm,” similar to those Russia used to influence the opinions of hundreds of millions of Facebook users in the 2020 campaign. Artificial intelligence could give these efforts a real boost.

There’s also evidence that China is using AI this cycle to spread malicious information about the U.S. One such social media post transcribed a Biden speech inaccurately to suggest he made sexual references.

AI may help election interferers do their dirty work, but new technology is hardly necessary for foreign meddling in U.S. politics.

In 1940, the United Kingdom – an American ally – was so focused on getting the U.S. to enter World War II that British intelligence officers worked to help congressional candidates committed to intervention and to discredit isolationists.

One target was the prominent Republican isolationist U.S. Rep. Hamilton Fish. Circulating a photo of Fish and the leader of an American pro-Nazi group taken out of context, the British sought to falsely paint Fish as a supporter of Nazi elements abroad and in the U.S.

Can AI be controlled?

Acknowledging that it doesn’t take new technology to do harm, bad actors can leverage the efficiencies embedded in AI to create a formidable challenge to election operations and integrity.

Federal efforts to regulate AI’s use in electoral politics face the same uphill battle as most proposals to regulate political campaigns. States have been more active: 19 now ban or restrict deepfakes in political campaigns.

Some platforms engage in light self-moderation. Google’s Gemini responds to prompts asking for basic election information by saying, “I can’t help with responses on elections and political figures right now.”

Campaign professionals may employ a little self-regulation, too. Several speakers at a May 2024 conference on campaign tech expressed concern about pushback from voters if they learn that a campaign is using AI technology. In this sense, the public concern over AI might be productive, creating a guardrail of sorts.

But the flip side of that public concern – what Stanford University’s Nate Persily calls “AI panic” – is that it can further erode trust in elections.

Barbara A. Trish does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Source: The Conversation

National Australia Bank says Nathan Goonan resigns as group CFO

National Australia Bank says Nathan Goonan resigns as group CFO

Going for gold: A look at the political and sporting challenges facing the next IOC president

Going for gold: A look at the political and sporting challenges facing the next IOC president

NZ house prices rise in February on improved buyer interest, REINZ says

NZ house prices rise in February on improved buyer interest, REINZ says

‘Massive gift to America’s enemies’: Activists decry cuts to government-funded networks

‘Massive gift to America’s enemies’: Activists decry cuts to government-funded networks

Liam Payne fans dedicate commemorative bench in Buenos Aires cemetery

Liam Payne fans dedicate commemorative bench in Buenos Aires cemetery

In Buenos Aires, thousands of faithful pray for Pope Francis

In Buenos Aires, thousands of faithful pray for Pope Francis

DOJ antitrust head targets pricey consultants amid DOGE cost cutting

DOJ antitrust head targets pricey consultants amid DOGE cost cutting

The Latest: Men's NCAA Tournament bracket revealed on Selection Sunday

The Latest: Men's NCAA Tournament bracket revealed on Selection Sunday

March Madness mascots take center stage during NCAA men's and women's tournaments

March Madness mascots take center stage during NCAA men's and women's tournaments