(CNN) — Alzheimer’s disease is increasingly widespread, affecting more than 55 million people worldwide — a figure that’s expected to nearly triple by 2050.

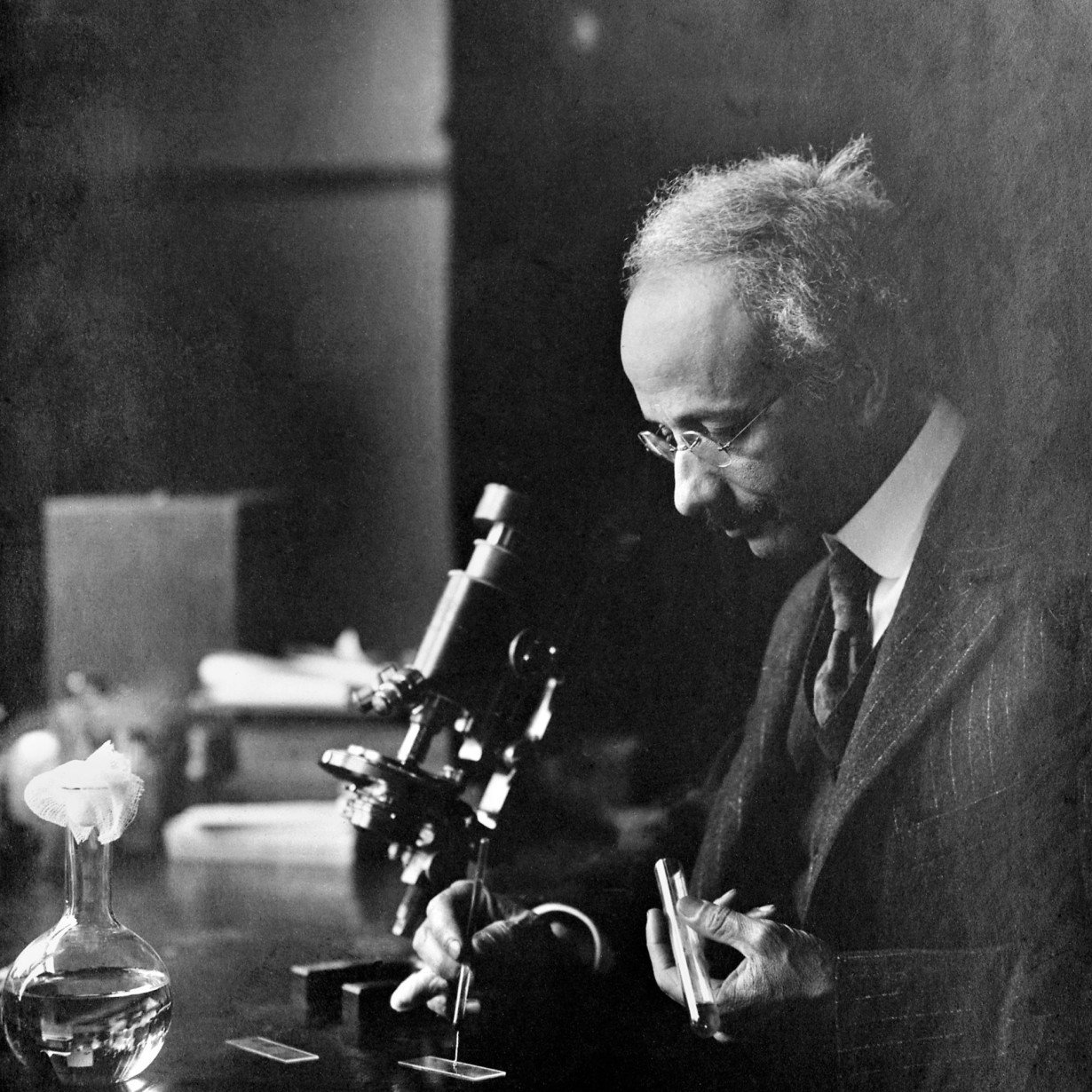

Despite the disease’s prevalence, few know the history of research on Alzheimer’s and the role played by an important yet long-overlooked figure: Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller, the first Black psychiatrist and neurologist in the United States.

Fuller’s work “not only advanced the understanding of Alzheimer’s disease, but also exemplified how diverse backgrounds and perspectives in medical research can drive scientific progress and improve patient care across different communities,” said Dr. Chantale Branson, associate professor of neurology at the Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta.

Fuller was born on August 11, 1872, in Monrovia, Liberia, to Solomon Fuller, a coffee planter and local government official, and Anna Ursula James. His paternal grandparents were formerly enslaved in Virginia before they bought their freedom and then immigrated to Liberia in 1852.

There, the couple helped establish a settlement for other freed African or African American people. His maternal grandparents were medical missionaries in Liberia, helping to ignite Fuller’s interest in medicine, Branson said.

That curiosity led a 17-year-old Fuller to move to the US, where he attended Livingstone College in North Carolina. He went on to study medicine at Long Island College Hospital in Brooklyn and earn a medical degree from Boston University in 1897, according to the university. Exploring Boston a few years earlier, Branson said, Fuller had walked into the institution and asked administrators to accept him as a medical student.

During a time of segregation that was merely 34 years since the Emancipation Proclamation but still nearly 70 before the Civil Rights Act, Fuller’s prevailing and obtaining his medical doctorate is a remarkable achievement.

But Fuller “was really one of those people who didn’t accept ‘no’ for an answer,” Branson recalled learning from a conversation she had with one of his family members a few years ago.

READ MORE: What Robin Williams’ widow wants you to know about the future of Lewy body dementia

Boston University was also the first US university to admit female students into the medical college, so it may have been more inclined than other institutions to be open to minorities at that time in history.

Highlighting the complexity of Alzheimer’s disease

Fuller then became a neuropathologist at Westborough State Hospital, a Massachusetts-based psychiatric hospital, where he performed autopsies throughout a two-year internship. His expertise earned him a Boston University faculty position as a full-time instructor in pathology in 1899, according to the university.

Desiring greater knowledge, Fuller connected with Bellevue Hospital in New York state, which had a pathology lab that was the envy of others in the field, said Dr. Tia Powell, clinical professor in the department of epidemiology and population health at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City.

A colleague advised Fuller that to further excel, he needed to go to Europe, where the level of science and medical education outperformed that of the US, added Powell, author of “Dementia Reimagined: Building a Life of Joy and Dignity from Beginning to End.”

In 1903, German researcher and pathologist Dr. Alois Alzheimer — whom the disease was eventually named after — was searching for foreign researchers who could assist him in brain research at his Royal Psychiatric Clinic lab at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in Germany. Fuller was one of only five scientists Alzheimer chose.

Alzheimer was interested in the normal and pathological anatomy of the brain’s cerebral cortex. So he and his team, including Fuller, used advanced techniques for preserving and staining brain tissues and cells to study them under a microscope, Powell said.

Multiple reports credit Fuller with the discovery of two brain abnormalities that are hallmark indicators of Alzheimer’s disease: neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques. The former are fibrous tangles made from the protein tau, whereas amyloid plaques are the buildup of beta amyloid, a protein that’s created during normal brain activity and accumulates as we age.

But Alzheimer was the first to discover and describe the tangles in 1906, following his autopsy of Auguste Deter, his former patient, experts said. At only age 51, Deter had been experiencing memory problems, disorientation and hallucinations. Alzheimer also noted that Deter’s cerebral cortex was thinner than normal, and that senile plaque was also present. He pioneered the leading theory on the culprit behind Alzheimer’s disease, which is that these tangles and plaques block nerve cells from communicating, eventually killing them.

What Fuller did, however, was challenge this notion, Powell said. Once Fuller returned to Westborough State Hospital, he discovered there were people who had died without having shown any symptoms of dementia yet had lots of plaques and tangles in their brains. The opposite was true for other patients.

Fuller argued that the plaques and tangles were therefore “neither necessary nor sufficient for what we would call dementia,” meaning there wasn’t always an easy correlation between those features and dementia, Powell said.

“It’s a pretty striking observation,” Powell added. “He’s a great scientist in that he looked at the data and he spoke very honestly about what he thought it proved and didn’t prove.

“And there are never enough scientists who really do that, who are willing to go against an argument put forward by their supervisors (and that there’s a growing consensus around),” Powell said. “It takes an incredibly brave and honest person who’s really accurate, who’s really careful about the conclusions he draws. And that, for any scientist, should be someone we see as a hero.”

The discrepancies Fuller noted remain an unsettled area in the study of dementia, experts said. Knowing more about the pathology of a disease helps doctors better understand when and how to prevent, test and treat it, Branson said.

Fuller was an early skeptic of the consensus on the causes of Alzheimer’s disease, but his work has long been overlooked, Powell said. Research for her book “was tempered with real sadness that as an academic psychiatrist, I had never heard of him,” she added. “In all the seemingly endless years of my training, he never came up once. … And there are many, many more skeptics now.”

In 1912, Fuller published the first comprehensive review of Alzheimer’s disease, experts said. He also founded and edited a research journal, the Westborough State Hospital Papers.

Fuller’s legacy

Fuller resigned from the hospital in 1919 then worked two associate professorships in pathology and neurology at Boston University. He remained there until 1933, when he retired after the university gave the neurology department chair position to a White man who was newly out of training and had just joined the faculty as an assistant professor, Branson said.

For five years, Fuller had served as chair of the department but was never given the title, according to the university.

“Fuller was paid less than his fellow professors who were white,” a Boston University article reports. “Fuller was unhappy, and said so: ‘With the sort of work that I have done, I might have gone farther and reached a higher plane had it not been for the colour of my skin,’ he wrote.”

Fuller went on to treat patients with syphilis at a veterans hospital in Tuskegee, Alabama, and train Black psychiatrists to treat Black World War I veterans. He was married to the renowned sculptor Meta Vaux Warrick, and they had three children. He became blind from diabetes in 1944 and died from the disease at age 80 in 1953.

The past several decades have seen Fuller’s contributions recognized in some respects. In 1969, the American Psychiatric Association created the annual Solomon Carter Fuller Award, which honors a Black person “who has pioneered in an area that has significantly improved the quality of life for black people.” The Black Psychiatrists of America established in 1974 the Solomon Carter Fuller Program for young Black psychiatrists. And in the same year, the Solomon Carter Fuller Mental Health Center opened in Boston. A middle school named after Fuller was built in 1994 in Framingham, Massachusetts, where he lived for many years.

“Diverse perspectives can challenge existing paradigms, promote creative thinking, and ultimately lead to breakthroughs that might otherwise be overlooked,” Branson said via email. “This is crucial in ensuring that medical research addresses the needs of diverse populations and leads to equitable healthcare solutions because ultimately, it will benefit the entire scientific community.”

People can lower their risk for Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of dementia by ensuring they get proper exercise, nutrition, social connection, engagement in activities, and sleep, Branson said. “Those neurofibrillary tangles or plaques are removed from the brain as people are sleeping.”

Managing stress is also important, as well as addressing any issues with eyesight or hearing by wearing glasses or hearing aids, respectively, Powell said.

“None of these things are perfect, but they all seem to make a contribution to (healthy cognition in old age),” Powell said.

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2025 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.

Researchers say the US government tried to erase sexual orientation from their findings

Researchers say the US government tried to erase sexual orientation from their findings

Violent clashes as Turkey protests continue over detention of Erdogan’s main political rival

Violent clashes as Turkey protests continue over detention of Erdogan’s main political rival

Under threat from Trump, Columbia University agrees to policy changes

Under threat from Trump, Columbia University agrees to policy changes

Homeland Security revokes temporary status for 532,000 Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans and Venezuelans

Homeland Security revokes temporary status for 532,000 Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans and Venezuelans

Trump administration cuts legal help for migrant children traveling alone

Trump administration cuts legal help for migrant children traveling alone

Twitter bird sign sells for nearly $35,000 at auction

Twitter bird sign sells for nearly $35,000 at auction

Canada's oldest company to liquidate all but 6 stores starting Monday

Canada's oldest company to liquidate all but 6 stores starting Monday

Duke star Cooper Flagg has a smooth March Madness debut in his return from an ankle injury

Duke star Cooper Flagg has a smooth March Madness debut in his return from an ankle injury

Rick Pitino and John Calipari share a mutual respect. Just don't call them friends

Rick Pitino and John Calipari share a mutual respect. Just don't call them friends

Ole Miss holds off frantic UNC comeback to beat Tar Heels 71-64 in NCAA Tournament

Ole Miss holds off frantic UNC comeback to beat Tar Heels 71-64 in NCAA Tournament