A heated debate has recently erupted between two groups of supporters of President Donald Trump. The dispute concerns the H-1B visa system, the program that allows U.S. employers to hire skilled foreign workers in specialty occupations – mostly in the tech industry.

On the one hand, there are people like Donald Trump’s former strategist Steve Bannon, who has called the H-1B program a “total and complete scam.” On the other, there are tech tycoons like Elon Musk who think skilled foreign workers are crucial to the U.S. tech sector.

The H-1B visa program is subject to an annual limit of new visas it can issue, which sits at 65,000 per fiscal year. There is also an additional annual quota of 20,000 H-1B visas for highly skilled international students who have a proven ability to succeed academically in the United States.

The H-1B program is the primary vehicle for international graduate students at U.S. universities to stay and work in the United States after graduation. At Rice University, where I work, much of STEM research is carried out by international graduate students. The same goes for most American research-intensive universities.

As a computer science professor – and an immigrant – who studies the interaction between computing and society, I believe the debate over H-1B overlooks some important questions: Why does the U.S. rely so heavily on foreign workers for the tech industry, and why is it not able to develop a homegrown tech workforce?

The US as a global talent magnet

The U.S. has been a magnet for global scientific talent since before World War II.

Many of the scientists who helped develop the atomic bomb were European refugees. After World War II, U.S. policies such as the Fulbright Program expanded opportunities for international educational exchange.

Attracting international students to the U.S. has had positive results.

Among Americans who have won the Nobel Prize in chemistry, medicine or physics since 2000, 40% have been immigrants.

In 2023, U.S.-born Louis Brus, left, shared the Nobel Prize in chemistry with U.S. immigrants Alexei Ekimov, born in the former USSR, and Moungi Bawendi, born in France.

Tech industry giants Apple, Amazon, Facebook and Google were all founded by first- or second-generation immigrants. Furthermore, immigrants have founded more than half of the nation’s billion-dollar startups since 2018.

Stemming the inflow of students

Restricting foreign graduate students’ path to U.S. employment, as some prominent Trump supporters have called for, could significantly reduce the number of international graduate students in U.S. universities.

About 80% of graduate students in American computer science and engineering programs – roughly 18,000 students in 2023 – are international students.

The loss of international doctoral students would significantly diminish the research capability of graduate programs in science and engineering. After all, doctoral students, supervised by principal investigators, carry out the bulk of research in science and engineering in U.S. universities.

It must be emphasized that international students make a significant contribution to U.S. research output. For example, scientists born outside the U.S. played key roles in the development of the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines. So making the U.S. less attractive to international graduate students in science and engineering would hurt U.S. research competitiveness.

Computing Ph.D. graduates are in high demand. The economy needs them, so the lack of an adequate domestic pipeline seems puzzling.

Where have US students gone?

So, why is there such a reliance on foreign students for U.S. science and engineering? And why hasn’t America created an adequate pipeline of U.S.-born students for its technical workforce?

After discussions with many colleagues, I have found that there are simply not enough qualified domestic doctoral applicants to fill the needs of their doctoral programs.

In 2023, for example, U.S. computer science doctoral programs admitted about 3,400 new students, 63% of whom were foreign.

It seems as if the doctoral career track is simply not attractive enough to many U.S. undergrad computer science students. But why?

The top annual salary in Silicon Valley for new computer science graduates can reach US$115,000. Bachelor’s degree holders in computing from Rice University have told me that until recently – before economic uncertainty shook the industry – they were getting starting annual salaries as high as $150,000 in Silicon Valley.

Doctoral students in research universities, in contrast, do not receive a salary. Instead, they get a stipend. These vary slightly from school to school, but they typically pay less than $40,000 annually. The opportunity cost of pursuing a doctorate is, thus, up to $100,000 per year. And obtaining a doctorate typically takes six years.

So, pursuing a doctorate is not an economically viable decision for many Americans. The reality is that a doctoral degree opens new career options to its holder, but most bachelor’s degree holders do not see beyond the economics. Yet academic computing research is crucial to the success of Silicon Valley.

A 2016 analysis of the information technology sectors with a large economic impact shows that academic research plays an instrumental role in their development.

Why so little?

The U.S. is locked in a cold war with China focused mostly on technological dominance. So maintaining its research-and-development edge is in the national interest.

Yet the U.S. has declined to make the requisite investment in research. For example, the National Science Foundation’s annual budget for computer and information science and engineering is around $1 billion. In contrast, annual research-and-development expenses for Alphabet, Google’s parent company, have been close to $50 billion for the past decade.

Universities are paying doctoral students so little because they cannot afford to pay more.

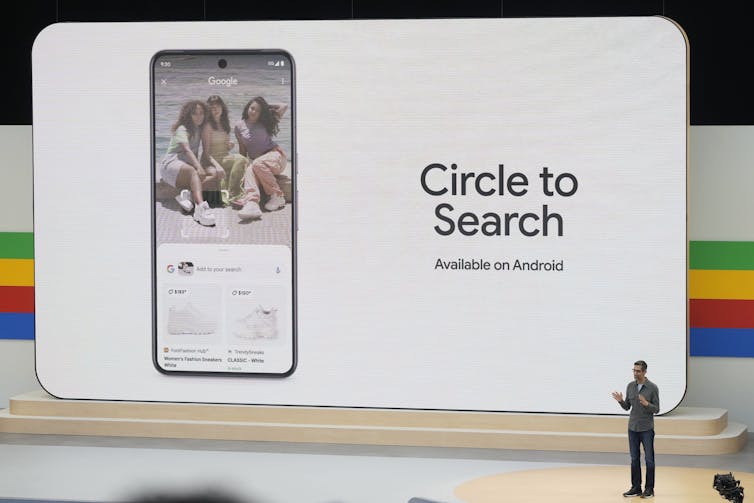

Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai speaks at a Google I/O event in Mountain View, Calif., on May 14, 2024.

But instead of acknowledging the existence of this problem and trying to address it, the U.S. has found a way to meet its academic research needs by recruiting and admitting international students. The steady stream of highly qualified international applicants has allowed the U.S. to ignore the inadequacy of the domestic doctoral pipeline.

The current debate about the H-1B visa system provides the U.S. with an opportunity for introspection.

Yet the news from Washington, D.C., about massive budget cuts coming to the National Science Foundation seems to suggest the federal government is about to take an acute problem and turn it into a crisis.

Moshe Y. Vardi receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the US Office of Naval Research.

Source: The Conversation

Canada's new prime minister is triggering an election campaign this weekend. Here’s what to know

Canada's new prime minister is triggering an election campaign this weekend. Here’s what to know

Trump has ordered the dismantling of the US Education Department. Here's what that means

Trump has ordered the dismantling of the US Education Department. Here's what that means

Rapper Yella Beezy charged with capital murder in shooting death of rapper Mo3

Rapper Yella Beezy charged with capital murder in shooting death of rapper Mo3

An ancient bronze griffin head is returned to Greece from New York in a major repatriation move

An ancient bronze griffin head is returned to Greece from New York in a major repatriation move

Most LAX – Heathrow flights cancelled as London airport closes after blaze

Most LAX – Heathrow flights cancelled as London airport closes after blaze

Texas measles outbreak expected to last for months, though vaccinations are up from last year

Texas measles outbreak expected to last for months, though vaccinations are up from last year

A NASA spacecraft will make another close pass of the sun

A NASA spacecraft will make another close pass of the sun

NYC will eventually have to abandon part of its water supply if it keeps getting saltier

NYC will eventually have to abandon part of its water supply if it keeps getting saltier

Georgia Amoore scores 34 points and Kentucky holds off charge by Liberty for 79-78 March Madness win

Georgia Amoore scores 34 points and Kentucky holds off charge by Liberty for 79-78 March Madness win