(CNN) — Colt’s Georgia homestead is far from finished. But in his depiction of life off the grid, digging holes and pulling weeds looks downright dreamy.

He excitedly documents the growth of his garlic, lemongrass and dandelion plants — crops that will attract pollinators and fill up his kitchen. He vigorously splits logs for firewood with a hatchet while his dog calmly sits nearby. He’s finally starting to lay the foundation for his new house, which he envisions as a “tiny home,” using an auger to drill holes into the tough Georgia red clay.

All the while, he’s typically dressed in a form-fitting dress, a shoulder-length wig and heeled boots (because open-toed shoes around hatchets and augers could spell disaster).

Colt is better known as “Rowdy Ruby,” a “homesteading drag queen with that good old queer audacity” and a following of over 400,000 across Instagram and TikTok. And among social media’s favorite homesteaders, or people who try to live self-sufficiently by growing their own food and living off land they own, Rowdy Ruby is a uniquely compelling figure — one who rejects the religious and “tradwife” values that often accompany homesteading. (Colt asked CNN to omit his last name to protect his privacy.)

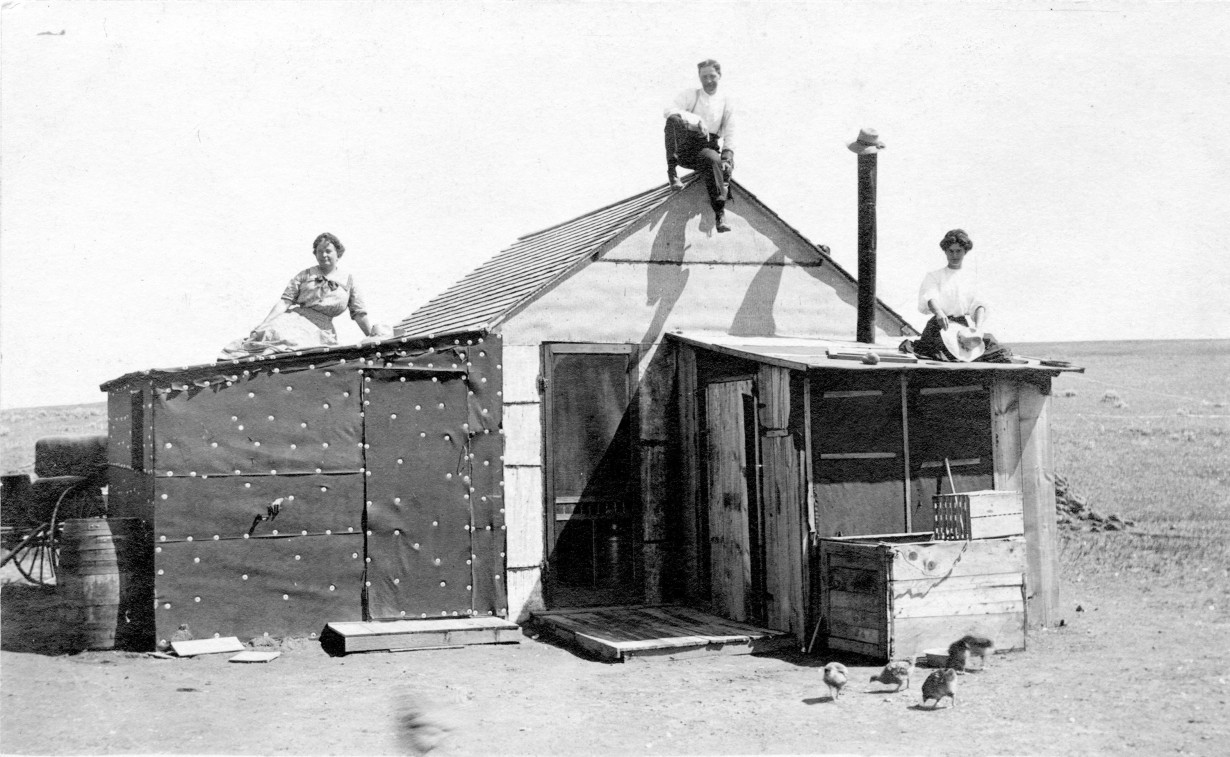

A drag queen may not comfortably fit the stereotypical homesteader mold. In the 19th century, homesteaders were Western pioneers who built new lives from necessity; on TikTok, the most popular homesteaders are often parents with young families or those with a lifelong connection to the practice, which often include so-called “tradwives,” or women who play a stereotypically gendered role in their family.

And yet queer and transgender people are finding a place in a lifestyle that, at least online, often occupies the same digital space as content from conservative creators, said Devin Proctor, an assistant professor of anthropology at Elon University in North Carolina who studies how we construct identities online.

“Whether through algorithms, exposure or privileged access, (social media) filtered the content and what rose to the top were pretty, White, blonde women,” Proctor said. “And a great many of the blonde White women in the online homesteading world happened to be Mormon, and thus skewed conservative.”

There’s room in homesteading for everyone, though, Colt said — it’s a way of life that requires hard work and a commitment to bettering the planet.

“The idea that conservatives are the only people capable of hard work — growing food, managing land — feels ridiculous for so many reasons,” Colt said. “It’s just a political belief system. What does that have to do with being able to build a house or manage a garden or cattle or chickens? What does that have to do with my ability to fell a tree?”

Queer homesteaders say the practice builds community

It took two years for Colt and his extended family to find the ideal land on which to spend the rest of their lives. They settled on 8 acres in northwest Georgia, next to a lake, where Colt, his siblings and other members of their family plan to grow their own food, build their own homes and restore the health of the land without pesticides or harmful practices.

“We wanted to build something that we’re really proud of — something away from the minted lawns of HOAs in suburbia, where they come to your porch and measure your plants,” Colt said.

On Rowdy Ruby’s homestead, nature rules. There will be no invasive plants on the property, and all native species, from songbirds to bats to beavers, are welcome. Colt and his family want to live with their land without depleting it, he said.

“I think a lot of people who get into homesteading, they’re doing it for the long game — they’re looking to set up generational wealth and self-sufficiency, which is a great thing to do,” Colt said. “I feel like there are very few homesteaders who get into it with nature in mind — thinking about themselves and not the ecosystems around it.”

Since the 1990s, homesteading has been understood as a “right-wing endeavor” meant to reject big-government interference and embrace independence, Proctor said.

“Homesteaders have always tended to be those left out of or fed up with society,” he said.

Many of the LGBTQ homesteaders who came to the practice as adults got into it to provide for themselves, but they’re not cutting themselves off from society, either.

“I think a lot of people come into homesteading out of a place of fear,” said River Evergreen, who lives in Washington state with their spouse, Juniper. “Homesteading gives the illusion of comfort for a lot of people that live in fear. So there does tend to be a bit of an isolationist mindset of like, ‘Well, I’m growing these crops, and they’re for me and my family, and I’m not going to make sure I don’t starve.’”

The Evergreens are taking the opposite approach to homesteading: They’re building a community.

The family is already starting to see the fruits of their labor, even if the trees aren’t producing anything edible yet. On their street, “free-spirited” dogs, pigs and chickens wander from yard to yard. Neighbors exchange seeds, fix each other’s chicken coops and feed each other’s children who wander up to the door for a snack.

“It feels a lot bigger than our small little acre,” Juniper Evergreen told CNN.

They envision their growing homestead becoming a safe space for LGBTQ Washingtonians, where they can gather and forage from the “edible food forest” the Evergreens are planning, or stay in a planned A-frame cabin they’re building, or even get married in a micro-orchard of fruit trees when they finally bloom.

The Evergreens may not live to see the full glory of what they grow. But that’s why they became homesteaders in the first place — to develop land that future generations will benefit from.

“We planted a redwood tree for our kids’ kids, because it’s so small that I’m not gonna enjoy it in its fullness in this lifetime,” River Evergreen said. “I didn’t plant it for me, and that’s okay. That has been invaluable in deepening my connection to the earth, my neighbors, the land and myself.”

The politics of homesteading have flip-flopped

Homesteaders themselves aren’t politically homogeneous. But the public understanding of homesteading as a political act has flip-flopped across the aisle since the 19th century.

The first generation of homesteaders practiced full self-sufficiency out of necessity, Proctor said. Under the 1862 Homestead Act, President Abraham Lincoln granted families 160 acres of land each, mainly west of the Mississippi River, with the expectation that families would tend to and live off the land. This grew the population of the West but destroyed the way of life Indigenous people had cultivated for millennia, though many contemporary homesteaders have reinstated Indigenous practices to tend their land.

Homesteading transformed again in the 1960s and ‘70s and became a countercultural movement. Anticapitalists and environmentalists “dropped out” of society by moving to rural areas, living off their own land and rejecting consumerism, Proctor said. They weren’t necessarily isolating themselves from society, either: Many of these homesteads became communes, where neighbors shared food.

Today’s most visible homesteaders may be attempting to live off the grid, but they’re incredibly plugged in online, where they upload curated videos of themselves making buttermilk with their children, harvesting fruits from their orchards or playing with new animal arrivals.

The public view of homesteading became politicized because homesteading content is “smuggled in with all the manner of other supposedly ‘traditional’ things” on TikTok, where it lives alongside “tradwife” content and other videos that reflect conservative values, Proctor said.

Ironically, though, many homesteaders on both ends of the political spectrum pursue homesteading for the same reason: To live life at a slower pace. Left- and right-leaning homesteaders, then, “make strange bedfellows for a perceived common cause,” Proctor said.

Take Grey and Grayson Prnce, a married couple who’ve been homesteading in New York’s Catskills Mountains for two years. They source their water from their local spring, churn their own butter and try to limit their electricity usage.

“But it doesn’t come from a separatist conservative mindset,” Grey Prnce told CNN. “It comes from an intense desire to live more sustainably and with community.”

Homesteading is for everyone, influencers say

Grayson Prnce was born into homesteading. The grandson of Mormon potato farmers in Idaho, Prnce grew up queer and trans in a religious environment for most of his life. When he distanced himself from that upbringing, he distanced himself from homesteading, too.

But when it came time to build their dream home, Prnce said he found himself relying on the same skills he tried to reject as a kid.

“I spent a lot of time trying to get away from how I was raised, and yet, in some ways, I’ve come back to it — just with a gay twist,” Prnce told CNN.

But the couple said their TikToks have courted some hateful comments from people who don’t think they don’t belong among viral homesteaders.

“It’s obvious that some people in the homesteading space just don’t like us nor expect us to be popping up on their feed,” Grey Prnce said. “Grayson is a visibly trans ex-Mormon married to a genderfluid Afro-Indigenous princess — I’m pretty sure we are a jump scare if you hate all those things.”

Even using the term “homesteaders” to describe themselves “is a very direct way of taking up space and correcting course,” Grey Prnce said.

“We shouldn’t be bullied out of the space because we want to take care of the planet, our communities, our health — physical and mental,” she said.

Colt said he’s heard from all kinds of homesteaders that his Ruby-fronted videos are a “breath of fresh air.” He’s glad to be a “safe person” for queer and trans homesteaders who want to get a sense of the practice from someone they can trust.

“They just want to learn how to bake bread,” he said. “They just want to learn how to grow crops from somebody that they feel like isn’t going to judge them, and they can get that from me.”

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2025 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.

Trump has begun another trade war. Here's a timeline of how we got here

Trump has begun another trade war. Here's a timeline of how we got here

Canada's leader laments lost friendship with US in town that sheltered stranded Americans after 9/11

Canada's leader laments lost friendship with US in town that sheltered stranded Americans after 9/11

Chinese EV giant BYD's fourth-quarter profit leaps 73%

Chinese EV giant BYD's fourth-quarter profit leaps 73%

You're an American in another land? Prepare to talk about the why and how of Trump 2.0

You're an American in another land? Prepare to talk about the why and how of Trump 2.0

Chalk talk: Star power, top teams and No. 5 seeds headline the women's March Madness Sweet 16

Chalk talk: Star power, top teams and No. 5 seeds headline the women's March Madness Sweet 16

Purdue returns to Sweet 16 with 76-62 win over McNeese in March Madness

Purdue returns to Sweet 16 with 76-62 win over McNeese in March Madness