By Luc Cohen

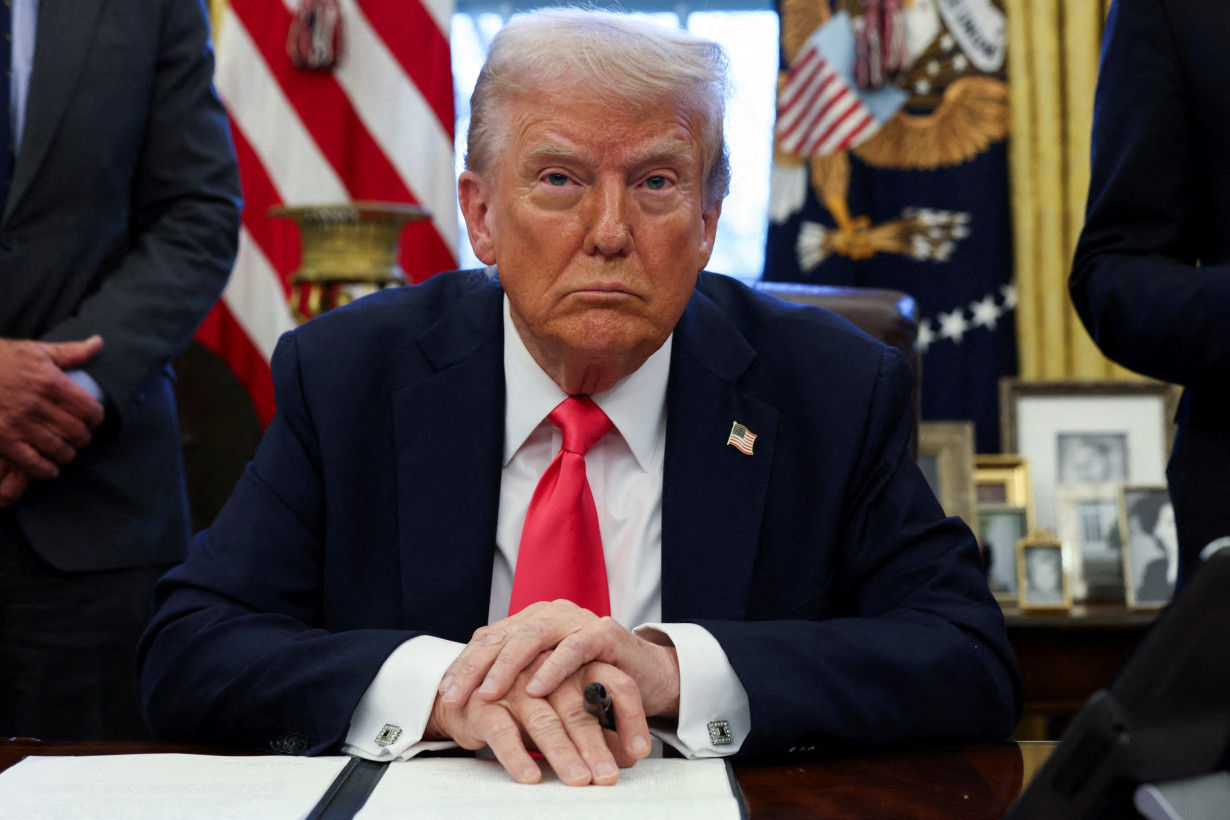

NEW YORK (Reuters) - U.S. President Donald Trump's designation of drug cartels as terrorist organizations heightens the risk of U.S. criminal prosecutions for American companies operating in parts of Latin America and migrants to the United States, legal experts said.

On February 19, the State Department designated the Sinaloa Cartel, Tren de Aragua, and six other Latin American criminal groups as global terrorist organizations, part of the Republican administration's crackdown on gangs it says are flooding the U.S. with drugs and helping migrants cross illegally.

In a memo on February 5 - after Trump had signaled his intent to label the cartels as terrorist groups, but before the designations were formally made - Attorney General Pam Bondi said the move would enable Justice Department prosecutors to charge cartel leaders with terrorism.

Six legal experts consulted by Reuters said the designations could also potentially leave U.S. companies and migrants who pay cartels for help crossing the border subject to prosecution for material support of a terrorist group under the U.S. criminal code.

The Justice Department and the White House did not respond to requests for comment.

To be sure, Reuters could not identify any prosecutions of companies under the statute in the week since the designations were implemented.

But former prosecutors said companies operating in parts of Mexico, where many companies have reported receiving demands for protection payments from organized crime groups, could be at risk of being charged if they make payments to groups now labeled terrorists. A 2024 study from the American Chamber of Commerce in Mexico of 218 companies showed 45% had received demands for protection payments.

"Companies need to know who they're dealing with and reassess that in light of these designations," said Brendan Quigley, a former federal prosecutor in Manhattan and current partner at law firm Baker Botts.

The risk of criminal prosecution also applies to non-U.S. companies with American operations, said Stephen Reynolds, a former federal prosecutor and current partner at law firm Day Pitney.

The Justice Department has in the past charged large companies with providing material support for groups the U.S. government labeled as terrorists in instances where the companies paid those organizations to be able to keep operating in territory they controlled.

In 2022, French cement maker Lafarge pleaded guilty in U.S. court and agreed to pay $778 million in forfeiture and fines over its Syrian subsidiary's $5.92 million in payments in 2013 and 2014, through intermediaries, to Islamic State and al Nusra Front after civil conflict broke out.

Lafarge's payments to the groups, designated terrorists by the U.S., were meant to allow the company's employees, customers and suppliers to pass through checkpoints, ultimately enabling it to earn $70 million in sales revenue from a plant it operated in northern Syria, prosecutors said.

Swiss-listed Holcim , which acquired Lafarge in 2015, did not respond to a request for comment. The company said in 2022 that the conduct "is in stark contrast with everything that Holcim stands for."

In her memo, Bondi said the Justice Department's foreign bribery unit would focus on cases involving cartels and other transnational criminal groups.

The designation of the cartels has "enormous implications" for U.S. businesses given the high volume of trade between the U.S. and Mexico, Central and South America, said Andrew Adams, a former federal prosecutor and current partner at law firm Steptoe. Mexico is the United States' largest trading partner, representing over 15% of total trade. The U.S. imported more than $475 billion of Mexican products in 2023.

Criminal prosecution is not the only risk.

U.S. law allows victims of violence by terrorist-designated groups, or relatives of those victims, to file civil claims in U.S. courts seeking damages from anyone deemed to have helped the group, said Carlton Greene, a partner at law firm Crowell & Moring and a former official in the Justice and Treasury Departments.

Last year, a Florida jury ordered banana producer Chiquita Brands International to pay $38.3 million in damages to the families of eight Colombian men killed by a paramilitary group that had been designated a terrorist organization by the U.S.

Chiquita is appealing the verdict. Its lawyers did not respond to a request for comment. It has said the paramilitary group threatened its workers, and that it made the payments to keep them safe.

POSSIBILITY FOR MORE SEVERE SENTENCES

The material support statute could also be used to prosecute migrants who paid someone linked to a cartel to help smuggle them across the U.S. border, or who send money back home to family members in areas with a heavy cartel presence, said Andrew Dalack, a lawyer with the Federal Defenders of New York.

"It could be used to really aggressively go after undocumented folks in particular for things that were not previously chargeable," Dalack said.

The designation enables prosecutors to charge someone caught moving a cartel's drugs with narcoterrorism, a crime carrying a 20-year mandatory prison sentence, said New York defense lawyer Zachary Margulis-Ohnuma.

That is double the 10-year mandatory minimum for possession with intent to distribute, a common charge in run-of-the-mill drug cases.

"It doubles the mandatory minimum for exactly the same conduct," Margulis-Ohnuma said.

(Reporting by Luc Cohen in New York; additional reporting by Sarah Kinosian in Mexico City; editing by Noeleen Walder and Nia Williams)

Trump has begun another trade war. Here's a timeline of how we got here

Trump has begun another trade war. Here's a timeline of how we got here

Canada's leader laments lost friendship with US in town that sheltered stranded Americans after 9/11

Canada's leader laments lost friendship with US in town that sheltered stranded Americans after 9/11

Chinese EV giant BYD's fourth-quarter profit leaps 73%

Chinese EV giant BYD's fourth-quarter profit leaps 73%

You're an American in another land? Prepare to talk about the why and how of Trump 2.0

You're an American in another land? Prepare to talk about the why and how of Trump 2.0

Chalk talk: Star power, top teams and No. 5 seeds headline the women's March Madness Sweet 16

Chalk talk: Star power, top teams and No. 5 seeds headline the women's March Madness Sweet 16

Purdue returns to Sweet 16 with 76-62 win over McNeese in March Madness

Purdue returns to Sweet 16 with 76-62 win over McNeese in March Madness