WASHINGTON (AP) — The Biden administration this week is expected to announce new automobile emissions standards that relax proposed limits for three years but eventually reach the same strict standards proposed by the Environmental Protection Agency.

The changes come as sales of zero-tailpipe emissions electric vehicles, needed to meet the standards, have begun to slow. The auto industry has cited lower sales growth in objecting to the EPA's preferred standards unveiled last April as part of the most ambitious plan ever to cut planet-warming emissions from passenger vehicles.

The EPA suggested that under its preferred alternative, the industry could meet the limits if 67% of new vehicle sales are electric by 2032.

But during a public comment period on the standards for 2027 through 2032, the auto industry called the benchmarks unworkable with EV sales slowing as consumers worry about cost, range and a lack of publicly available charging stations.

Three people with knowledge of the standards say the Biden EPA will pick an alternative that slows implementation from 2027 through 2029, but ramps up to reach the level the EPA preferred from 2030 to 2032. The alternative will have other modifications that help the auto industry meet the standards, including the calculation of how EV fuel economy is measured, one of the people said.

The people, two from the auto industry and one from the government, didn’t want to be identified because the new standards haven’t been made public by the EPA.

The changes appear aimed at addressing strong industry opposition to the accelerated ramp-up of EVs, along with public reluctance to fully embrace the new technology. There is also a legitimate threat of legal challenges before conservative courts.

The Supreme Court, with a 6-3 conservative majority, has increasingly reined in the powers of federal agencies, including the EPA, in recent years. The justices have restricted the EPA’s authority to fight air and water pollution — including a landmark 2022 ruling that limited the EPA’s authority to regulate carbon dioxide emissions from power plants that contribute to global warming.

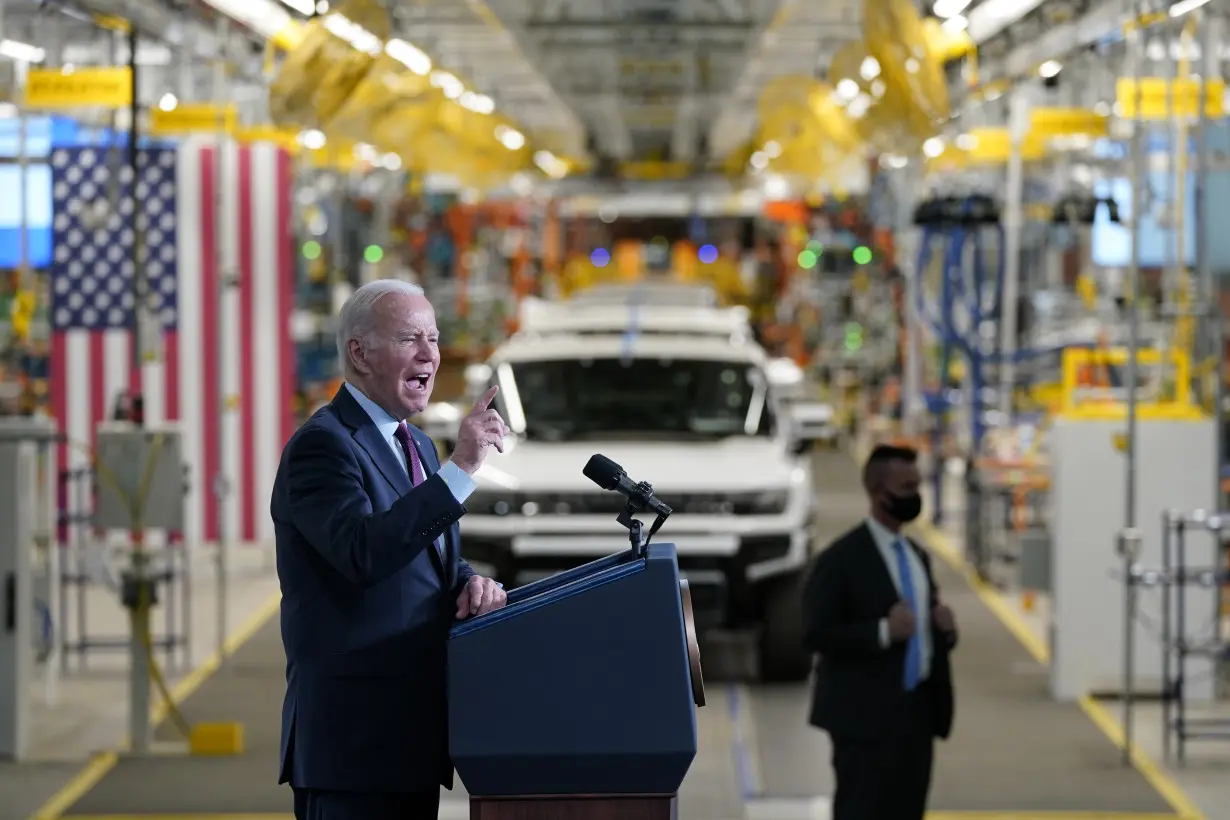

Biden has made fighting climate change a hallmark of his presidency and is seeking to slash carbon dioxide emissions from gasoline-powered vehicles, which make up the largest single source of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.

At the same time, Biden needs cooperation from the auto industry and political support from auto workers, a key political voting bloc. The United Auto Workers union, which has endorsed Biden, has said it favors the transition to electric vehicles but wants to make sure jobs are preserved and that industry pays top wages to workers who build the EVs and batteries.

Generally, environmental groups have been optimistic about the new EPA plan.

Manish Bapna, president of Natural Resources Defense Council, told reporters last week that he expects the rule will significantly cut carbon emissions from cars and light-duty trucks, which are the source of one-fifth of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions.

“Based on what we hear, there’s no reason to doubt that the climate rules for cars and light-duty trucks are going to cut well over 90% of the carbon pollution from new cars, SUVs and pickup trucks’’ over the next few decades, Bapna said. “That’s huge.″

Between 2027 and 2055, the EPA rule “will prevent more than 70 billion tons of climate wrecking carbon emissions. That’s more than the nation generates in a year. It’s absolutely essential, real, concrete progress,’’ Bapna said.

“EPA’s clean car standards will put the pedal to the metal as the U.S. races to achieve cleaner, healthier air for everyone,” said Amanda Leland, executive director of Environmental Defense Fund, another environmental group.

Tailpipes release dangerous particle pollution and smog and are one of the largest sources of climate pollution in the nation, Leland said. “Strong clean car standards help provide cleaner air and a safer climate, thousands of dollars in cost savings for our families and hundreds of thousands of new jobs in U.S. manufacturing.″

Luke Tonachel, an automobile expert with the Natural Resources Defense Council, said the new clean-car standards will encourage the auto industry to “continue investing, as it’s already starting to do, over the long-term period″ in EV and zero-emission vehicles. The rule also will send a signal to infrastructure providers and utilities to keep building out the charging infrastructure,’’ he said.

But Dan Becker at the Center for Biological Diversity, said he fears loopholes will let the industry continue to sell gas burners. He also is afraid the industry will get off with doing little during the first three years of the standards, which could be undone if Donald Trump is elected president.

“The bottom line is that the administration is caving to pressure from big oil, big auto and the dealers to stall progress on EVs and now allow more pollution from cars,” Becker said.

At a Detroit-area rally in September, Trump insisted Biden’s embrace of electric vehicles — a key component of his clean-energy agenda — would ultimately lead to lost jobs. “He’s selling you out to China, he’s selling you out to the environmental extremists and the radical left,” Trump told his crowd.

Republicans and some in the industry have said the rule would require that 67% of new vehicle sales be electric by 2032, forcing people to buy cars, trucks and SUVs that they aren't yet ready to accept.

But EPA Administrator Michael Regan has said the new rule is a performance standard that leaves it to industry to come up with solutions.

U.S. electric vehicle sales grew 47% last year to a record 1.19 million as EV market share rose from 5.8% in 2022 to 7.6%. But EV sales growth slowed toward the end of the year. In December, they rose 34%.

The Alliance for Auto Innovation, a large industry trade group, said in a news release that the ramp up to 67% initially proposed by the EPA is too fast for the industry to achieve. The EPA's pace of EV adoption is faster than President Joe Biden's goal of electric vehicles being half of U.S. new vehicle sales by 2030, the group said.

“Where we are (or aren’t) in 2032 is unclear at this point,” the group said. “But moderating the pace of EV adoption in 2027, 2028, 2029 and 2030 would be the right call because it prioritizes more reasonable and achievable electrification targets in the next few (very critical) years.”

The EPA's preferred standards take carbon dioxide emissions from 152 grams per mile in 2026 to 73 in 2032, a 52% reduction. The limits would reach 99 grams per mile by 2029.

But under the alternative that environmental groups expect the EPA to adopt, the standards would be eased in the first three years, reaching 112 grams by 2029 but still hitting 73 in 2032.

____

AP Auto Writer Tom Krisher reported from Detroit.

China blacklists four U.S. companies for involvement in arms sales to Taiwan

China blacklists four U.S. companies for involvement in arms sales to Taiwan

China, Sri Lanka agree more investment and economic cooperation

China, Sri Lanka agree more investment and economic cooperation

Brazil's Gol releases new five-year plan ahead of Chapter 11 exit

Brazil's Gol releases new five-year plan ahead of Chapter 11 exit

Poland's leader accuses Russia of planning acts of terror against 'airlines over the world'

Poland's leader accuses Russia of planning acts of terror against 'airlines over the world'

Portugal's growth likely accelerating, finance minister says

Portugal's growth likely accelerating, finance minister says

Italy's Salvini faces calls to quit over late-running trains

Italy's Salvini faces calls to quit over late-running trains

Look of the Week: Timothée Chalamet adopts London’s most stylish accessory

Look of the Week: Timothée Chalamet adopts London’s most stylish accessory

Texas online porn age-verification law goes to US Supreme Court

Texas online porn age-verification law goes to US Supreme Court