Are democratic societies ready for a future in which AI algorithmically assigns limited supplies of respirators or hospital beds during pandemics? Or one in which AI fuels an arms race between disinformation creation and detection? Or sways court decisions with amicus briefs written to mimic the rhetorical and argumentative styles of Supreme Court justices?

Decades of research show that most democratic societies struggle to hold nuanced debates about new technologies. These discussions need to be informed not only by the best available science but also the numerous ethical, regulatory and social considerations of their use. Difficult dilemmas posed by artificial intelligence are already emerging at a rate that overwhelms modern democracies’ ability to collectively work through those problems.

Broad public engagement, or the lack of it, has been a long-running challenge in assimilating emerging technologies, and is key to tackling the challenges they bring.

Ready or not, unintended consequences

Striking a balance between the awe-inspiring possibilities of emerging technologies like AI and the need for societies to think through both intended and unintended outcomes is not a new challenge. Almost 50 years ago, scientists and policymakers met in Pacific Grove, California, for what is often referred to as the Asilomar Conference to decide the future of recombinant DNA research, or transplanting genes from one organism into another. Public participation and input into their deliberations was minimal.

Societies are severely limited in their ability to anticipate and mitigate unintended consequences of rapidly emerging technologies like AI without good-faith engagement from broad cross-sections of public and expert stakeholders. And there are real downsides to limited participation. If Asilomar had sought such wide-ranging input 50 years ago, it is likely that the issues of cost and access would have shared the agenda with the science and the ethics of deploying the technology. If that had happened, the lack of affordability of recent CRISPR-based sickle cell treatments, for example, might’ve been avoided.

AI runs a very real risk of creating similar blind spots when it comes to intended and unintended consequences that will often not be obvious to elites like tech leaders and policymakers. If societies fail to ask “the right questions, the ones people care about,” science and technology studies scholar Sheila Jasanoff said in a 2021 interview, “then no matter what the science says, you wouldn’t be producing the right answers or options for society.”

Even AI experts are uneasy about how unprepared societies are for moving forward with the technology in a responsible fashion. We study the public and political aspects of emerging science. In 2022, our research group at the University of Wisconsin-Madison interviewed almost 2,200 researchers who had published on the topic of AI. Nine in 10 (90.3%) predicted that there will be unintended consequences of AI applications, and three in four (75.9%) did not think that society is prepared for the potential effects of AI applications.

Who gets a say on AI?

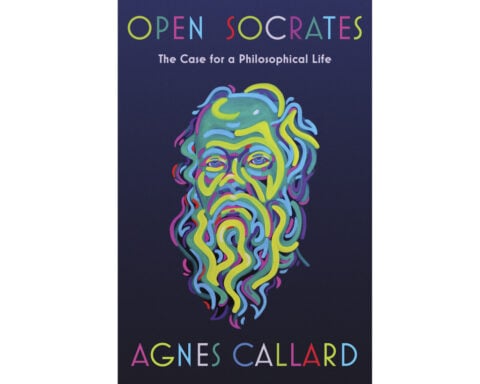

Industry leaders, policymakers and academics have been slow to adjust to the rapid onset of powerful AI technologies. In 2017, researchers and scholars met in Pacific Grove for another small expert-only meeting, this time to outline principles for future AI research. Senator Chuck Schumer plans to hold the first of a series of AI Insight Forums on Sept. 13, 2023, to help Beltway policymakers think through AI risks with tech leaders like Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg and X’s Elon Musk.

Meanwhile, there is a hunger among the public for helping to shape our collective future. Only about a quarter of U.S. adults in our 2020 AI survey agreed that scientists should be able “to conduct their research without consulting the public” (27.8%). Two-thirds (64.6%) felt that “the public should have a say in how we apply scientific research and technology in society.”

The public’s desire for participation goes hand in hand with a widespread lack of trust in government and industry when it comes to shaping the development of AI. In a 2020 national survey by our team, fewer than one in 10 Americans indicated that they “mostly” or “very much” trusted Congress (8.5%) or Facebook (9.5%) to keep society’s best interest in mind in the development of AI.

A healthy dose of skepticism?

The public’s deep mistrust of key regulatory and industry players is not entirely unwarranted. Industry leaders have had a hard time disentangling their commercial interests from efforts to develop an effective regulatory system for AI. This has led to a fundamentally messy policy environment.

Tech firms helping regulators think through the potential and complexities of technologies like AI is not always troublesome, especially if they are transparent about potential conflicts of interest. However, tech leaders’ input on technical questions about what AI can or might be used for is only a small piece of the regulatory puzzle.

Much more urgently, societies need to figure out what types of applications AI should be used for, and how. Answers to those questions can only emerge from public debates that engage a broad set of stakeholders about values, ethics and fairness. Meanwhile, the public is growing concerned about the use of AI.

AI might not wipe out humanity anytime soon, but it is likely to increasingly disrupt life as we currently know it. Societies have a finite window of opportunity to find ways to engage in good-faith debates and collaboratively work toward meaningful AI regulation to make sure that these challenges do not overwhelm them.

Dietram A. Scheufele is affiliated with the Morgridge Institute for Research, a biomedical research organization, which provides financial support to The Conversation.

Dominique Brossard is affiliated with the Morgridge Institute for Research, a biomedical research organization, which provides financial support to The Conversation.

Todd Newman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Joann files for bankruptcy — again

Joann files for bankruptcy — again

German economy, Europe’s largest, shrinks for second straight year

German economy, Europe’s largest, shrinks for second straight year

Supreme Court will hear Texas anti-pornography law that challengers say violates free-speech rights

Supreme Court will hear Texas anti-pornography law that challengers say violates free-speech rights

Comoros ruling party wins parliamentary elections, opposition rejects results

Comoros ruling party wins parliamentary elections, opposition rejects results

Sweden seeks to change constitution to be able to revoke citizenships

Sweden seeks to change constitution to be able to revoke citizenships

Confused about all the tax changes in the past decade? Just wait

Confused about all the tax changes in the past decade? Just wait

US inflation likely remained elevated last month, threatening interest rate cuts

US inflation likely remained elevated last month, threatening interest rate cuts

Coors Light is changing its name

Coors Light is changing its name

Tiger Woods’ son Charlie chuckles while watching his dad suffer heavy defeat in TGL debut

Tiger Woods’ son Charlie chuckles while watching his dad suffer heavy defeat in TGL debut

Bayern Munich signs US youngster Bajung Darboe from LAFC

Bayern Munich signs US youngster Bajung Darboe from LAFC

Tech leaders like Alphabet CEO Sundar Picha and OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, seen here entering the White House, are just one piece of the AI regulation puzzle.

Tech leaders like Alphabet CEO Sundar Picha and OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, seen here entering the White House, are just one piece of the AI regulation puzzle.