Top Articles

Demonstrators gather at UCLA amid reports of student detained by CPB

Kings set to face Oilers in round one of Stanley Cup Playoffs: preview

US News

See all »Key takeaways from Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs

Hear Trump break down tariffs on various countries

‘The most powerful type of liar’: Tapper asks Anna Delvey how she views her criminal past

Tornadoes, heavy rains rip across central, southern US

World News

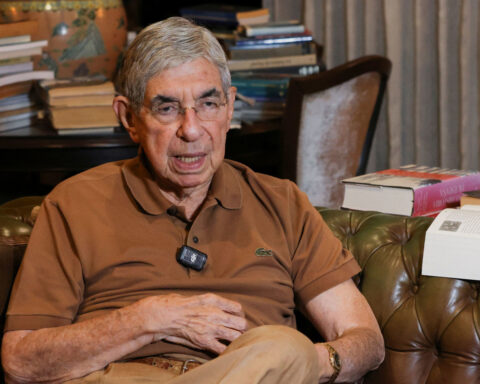

See all »Former Costa Rican president who compared Trump to ‘Roman emperor’ says US has revoked his visa

Israel to seize parts of Gaza as military operation expands

World leaders react to Trump's tariffs

A wary Europe awaits Rubio with NATO's future on the line

Latest

US Treasury's Bessent urges IMF, World Bank to refocus on core missions

Wall Street ends higher on earnings, hopes of easing tariff tensions

U.S. stocks rebounded on Tuesday as a spate of quarterly earnings reports and hints at the de-escalation of U.S.-China trade tensions brought buyers in from the sidelines.

See the moment Vatican announces death of Pope Francis

A video released by Vatican media shows the moment the pope's death was announced on Monday morning by Cardinal Kevin Farrell, the Vatican camerlengo. The camerlengo — or chamberlain — is the acting head of the Vatican in the period between the death or resignation of a pope and appointment of the next leader of the Catholic Church.

Former CDC official reveals why he left after RFK Jr. took over

Trump said he didn’t sign controversial proclamation. The Federal Register shows one with his signature

President Donald Trump downplayed his involvement in invoking the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to deport Venezuelan migrants, saying for the first time that he hadn’t signed the proclamation, but that he stood by his administration’s move. The proclamation invoking the Alien Enemies Act appears in the Federal Register with Trump’s signature at the bottom. CNN’s Kaitlan Collins reports.

Cory Booker’s historic speech energizes a discouraged Democratic base

Cory Booker’s historic speech energizes a discouraged Democratic base

Trump's tariffs roil company plans, threatening exports and investment

Stock futures plunge as investors digest Trump’s tariffs

Stock futures plunge as investors digest Trump’s tariffs

Hear Trump break down tariffs on various countries

President Donald Trump announced during a speech at the White House plans for reciprocal tariffs. A group of countries will be charged a tariff at approximately half the rate they charge the United States.

Attorney for father deported in 'error' says this is what's 'new, unique and terrifying' about case

CNN's Erin Burnett speaks with Simon Sandoval-Moshenberg, the attorney for a Maryland father the Trump administration conceded it mistakenly deported to El Salvador “because of an administrative error.”

California & Local

See all »Pope Francis dies at the Vatican at age 88

Kings set to face Oilers in round one of Stanley Cup Playoffs: preview

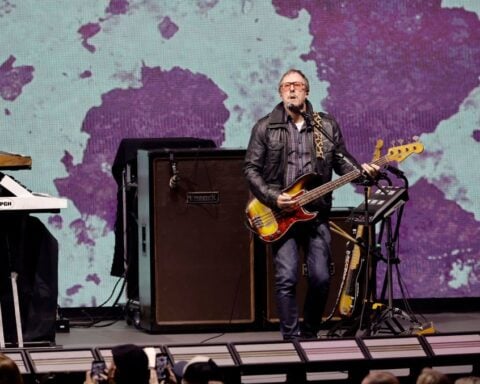

Weezer bassist to play Coachella despite wife’s arrest

Technology

See all »TSMC shows off new tech for stitching together bigger, faster chips

Elon Musk’s government role gets even murkier

Tesla exec cancels Rome conference trip over security concerns

Lifestyle

See all »Pastor calls for 'full Target boycott' over concerns about diversity, equity, inclusion

Trump is putting his 'touches' on the White House with flagpoles, art and an Oval Office overhaul

Metabolic syndrome is a big risk factor for early dementia, and what you do makes a difference, study suggests

How residents plan to preserve the memory of an iconic landmark

Entertainment

See all »On the brink of the NFL draft, the biggest question surrounds Shedeur Sanders and where he's going

Welcome to Green Bay: NFL prospects begin to arrive in Wisconsin for the Draft

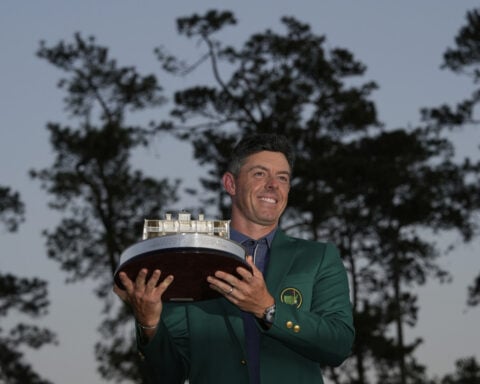

Rory McIlroy wouldn't let a cold or Masters fatigue keep him from a Zurich Classic title defense

Jennifer Aniston cheekily acknowledges her Easter egg cameo on ‘The Last of Us’

Trump has begun another trade war. Here's a timeline of how we got here

Trump has begun another trade war. Here's a timeline of how we got here

Canada's leader laments lost friendship with US in town that sheltered stranded Americans after 9/11

Canada's leader laments lost friendship with US in town that sheltered stranded Americans after 9/11

Chinese EV giant BYD's fourth-quarter profit leaps 73%

Chinese EV giant BYD's fourth-quarter profit leaps 73%

You're an American in another land? Prepare to talk about the why and how of Trump 2.0

You're an American in another land? Prepare to talk about the why and how of Trump 2.0

Chalk talk: Star power, top teams and No. 5 seeds headline the women's March Madness Sweet 16

Chalk talk: Star power, top teams and No. 5 seeds headline the women's March Madness Sweet 16

Purdue returns to Sweet 16 with 76-62 win over McNeese in March Madness

Purdue returns to Sweet 16 with 76-62 win over McNeese in March Madness