On a quiet February morning in 1981, 16-year-old Sherry Parsons' life was shattered when she discovered her mother, Barbara, brutally murdered in their Norwalk, Ohio, home. As per Forensic Evidence the blood-soaked scene was horrific – Barbara's nightgown and bedsheets were drenched in blood that covered the walls and ceiling. Despite her husband James having an alibi, police zeroed in on him as the prime suspect based on circumstantial evidence.

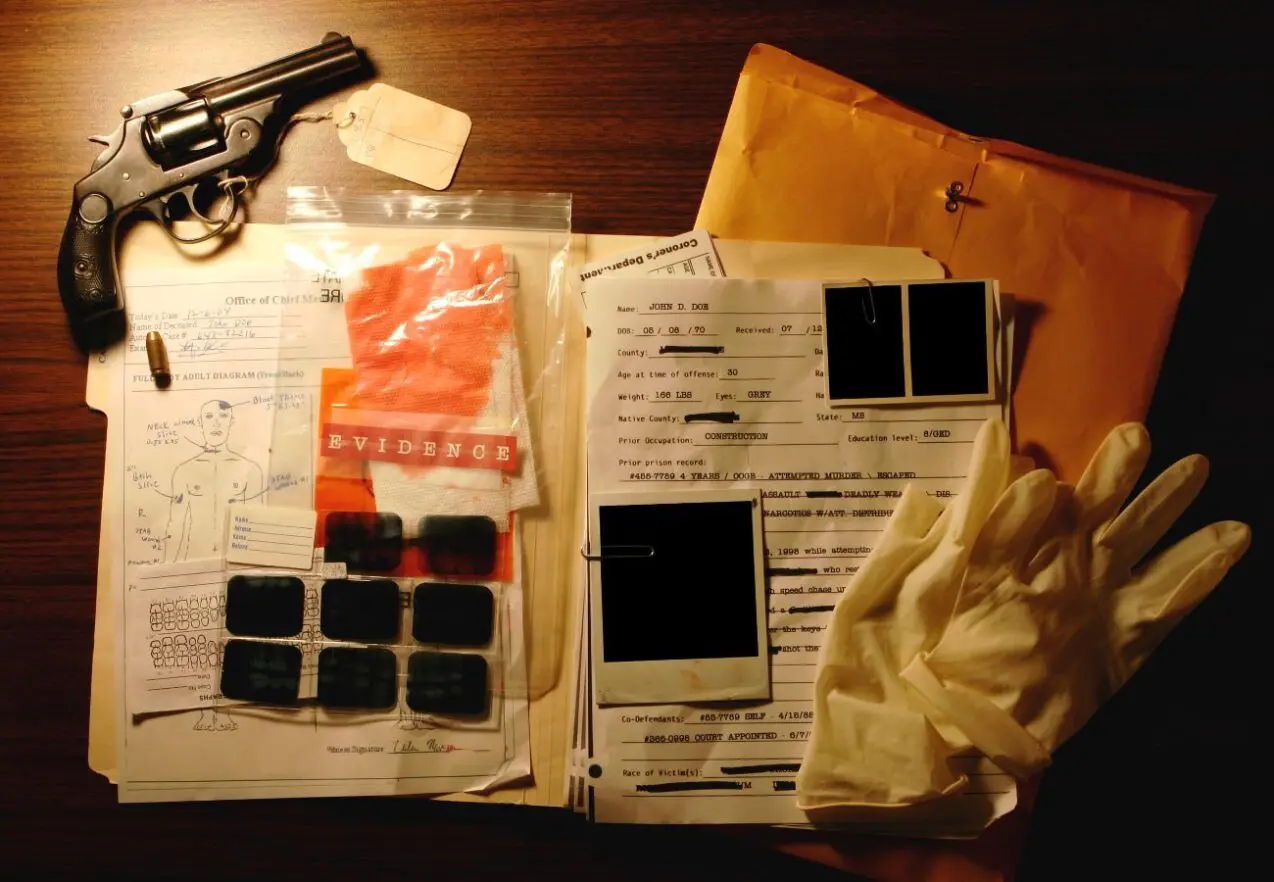

Over a decade later, an intriguing clue emerged. A Craftsman breaker bar – a heavy tool used to unscrew bolts – retrieved from a car James once owned was suspected as the murder weapon. The case hinged on bloodstain analysis by veteran forensic analyst G. Michele Yezzo, who controversially claimed identifying characteristics on the nightgown and bedsheet matched the Craftsman logo.

In 1993, largely based on Yezzo's testimony providing the crucial physical link, James Parsons was convicted of murdering his wife and sentenced to 15 years to life in prison. The prosecution portrayed Yezzo's findings as "uncontroverted," the jury accepted her expert opinion as definitive evidence.

However, two decades later, a re-examination of the case exposed deeply concerning issues with Yezzo's credibility and the quality of her forensic work. In 2013, the Ohio Innocence Project requested Yezzo's personnel file from the Bureau of Criminal Investigation (BCI), where she worked. The 449-page file revealed a lengthy pattern of troubling behavior and serious allegations that questioned her competence and impartiality.

According to court filings, Yezzo has a history of violent outbursts, using racial insults, threatening coworkers, and having a "reputation of giving dept. answer it wants if you stroke her." Prompts cautioned that her "findings and conclusions. maybe suspect," and her "interpretational and observational errors" sparked worries from supervisors that "could lead to a substantial miscarriage of justice."

Crucially, Yezzo had been placed on administrative leave due to these issues just two months before testifying in Parsons' trial. She was quickly reinstated with no disclosure to the defense about the disciplinary action or doubts over her credibility and potential bias favoring law enforcement.

In 2016, presented with the personnel file findings, a judge vacated Parsons' conviction, declaring "these failures undermined his right to a fair trial" and the guilty verdict as "unworthy of confidence." James Parsons was released after 23 years of suffering from health issues. He died just ten months later at age 79.

The Parsons case exemplifies the inherent dangers when prosecutors portray forensic analysis of questionable validity as unimpeachable proof and juries view it as such. Too often, the persuasive allure of forensic "science" can wrongfully deprive innocent people of their freedom based on unsubstantiated methods or tainted testimony.

Flawed and unreliable forensic techniques like bloodstain pattern analysis have repeatedly contributed to wrongful convictions across the country. A 2009 landmark report criticized many forensic disciplines for lacking consistent standards, scientific validation, and proper oversight – the sole exception being DNA analysis.

The criminal justice system grants forensic experts an "imprimatur of expertise and certainty" that can unduly sway judges and juries. Yet numerous studies exposing high error rates for various forensic methods, such as bite mark comparisons, hair analysis, and bloodstain interpretation, undercut this credibility.

Cognitive bias also remains a pervasive issue, with experts unconsciously influenced by external details like a defendant's race, religion, or criminal record. In one case, FBI examiners were swayed to misidentify a print after learning about Brandon Mayfield's Muslim faith. This mistake led to his wrongful imprisonment until Spanish investigators identified the true source.

Perhaps most alarmingly, the self-governing forensic community lacks independence. Most crime labs are nestled under law enforcement control and accountable to prosecutors' offices for funding. This fosters an unhealthy "team" mentality and tacit confirmatory biases that can eclipse neutral scientific rigor in adversarial legal proceedings.

While isolated rogue analysts exist, Yezzo's story reveals the deeper systemic pitfalls of overreliance on forensic analysis of unproven reliability from experts operating in an insular law enforcement environment with minimal outside oversight or quality control. The "blizzard of errors" from misapplied forensics has led to many wrongful convictions.

Reform efforts like the proposed creation of independent crime labs and enforceable standards have languished amid opposition. Only a handful of states, like Texas, have enacted laws enabling the convicted to challenge tainted forensics. For many like Kevin Keith – whose death sentence was commuted by Ohio's governor amid concerns over Yezzo's testimony – restrictive laws have foreclosed judicial relief despite compelling evidence of innocence.

The Parsons case underscores why convictions secured through forensic evidence must be consistently reevaluated through a rigorous lens of scientific skepticism. Forensic analysis can be a vital investigative tool, but when presented as infallible proof rather than rebuttable opinion, it can lead to staggering injustices. Robust systemic changes are crucial to restore credibility and mitigate the potential for tainted or misconstrued forensics to corrupt the truth-seeking mission of the justice system.

India considers cutting personal income tax to lift consumption, sources say

India considers cutting personal income tax to lift consumption, sources say

Russia arrests 4 suspects accused of plotting to kill top military officers on Ukraine's orders

Russia arrests 4 suspects accused of plotting to kill top military officers on Ukraine's orders

Azerbaijan observes day of mourning for air crash victims as speculation mount about its cause

Azerbaijan observes day of mourning for air crash victims as speculation mount about its cause

China's Xi sends condolences over Azerbaijan Airlines plane crash

China's Xi sends condolences over Azerbaijan Airlines plane crash

UNIFIL urges timely Israeli pullout from south Lebanon under month-old truce deal

UNIFIL urges timely Israeli pullout from south Lebanon under month-old truce deal

Japan's Nippon Steel extends closing date for U.S. Steel acquisition

Japan's Nippon Steel extends closing date for U.S. Steel acquisition

BYD contractor denies 'slavery-like conditions' claims by Brazilian authorities

BYD contractor denies 'slavery-like conditions' claims by Brazilian authorities

Kazakhstan's senate chief: cause of Azerbaijan Airlines plane crash unknown for now

Kazakhstan's senate chief: cause of Azerbaijan Airlines plane crash unknown for now

Durant and Beal score 27 points each, Suns beat Nuggets 110-100 to close out Christmas slate

Durant and Beal score 27 points each, Suns beat Nuggets 110-100 to close out Christmas slate