Immigration is already a major polarizing issue in the 2024 U.S. presidential election. Arrests for illegal border crossings from Mexico reached an all-time high in December 2023, and cities like New York and Chicago are struggling to provide housing and basic services for tens of thousands of migrants arriving from Texas.

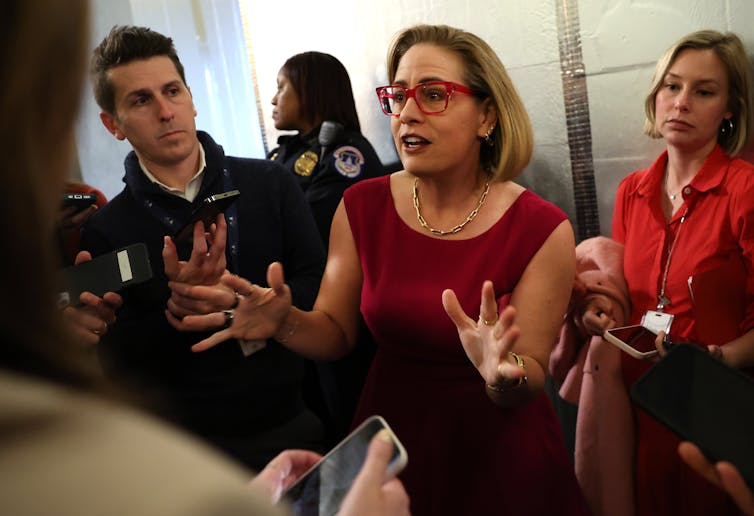

In early February 2024, a group of senators proposed new immigration legislation that would have slowed the migrant influx at the border. The bill would have made it harder for migrants to both apply for and receive asylum, which is the legal right to stay in the U.S. because of fear of persecution if they return back home. But the bill, like others proposed in recent years, quickly faltered after Republicans opposed it.

This is far from the first time that Democrats and Republicans have failed to pass legislation that was intended to improve the country’s immigration system.

I am a scholar of immigration and refugee policy. Here are four key reasons why meaningful immigration policy change has been so difficult to achieve – and why it remains a pipe dream:

1. Immigration reform has always been hard

The U.S. has faced major roadblocks every time it has tried to achieve immigration reform.

For decades after World War II, presidents, lawmakers and activists tried and failed to revamp the nation’s immigration system to remove racist quotas based on national origin, set in the 1920s, that restricted all but northern and western Europeans from immigrating to the U.S.

Change finally came in 1965, when Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act. This required extensive negotiations. The final bipartisan bargain removed racist quotas but appeased those who wanted to restrict immigration by prioritizing new immigrants’ connections to family already in the country – a preference that lawmakers thought would favor Europeans.

The last big immigration reform happened in 1986, when Congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act. Year after year, throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Congressional bills to address the porous border with Mexico and the undocumented immigrant population living in the country went nowhere. After many false starts, an uneasy Left-Right majority finally agreed in 1986 on a package that sanctioned employers who hired undocumented immigrants, provided legal status to roughly 3 million undocumented migrants, created a new farmworker program, and increased border security resources.

For almost four decades, Washington has been stuck in neutral on this issue.

2. The US is more polarized on immigration than ever before

Americans have been at odds over how to handle immigration since the nation’s founding. But partisan and ideological polarization over border control and immigrants’ rights is greater today than any other time.

Over the past 20 years, Democratic and Republican voters and politicians alike became more firmly aligned with rival pro- and anti-immigration rights movements.

In 2008, 46% of Republicans and 39% of Democrats said they thought immigration to the U.S. should be decreased. In 2023, GOP support for decreased immigration soared to 73%, compared with just 18% of Democrats who said they wanted that. Today, Republicans are almost three times as likely as Democrats to see b vc immigration as a very big national problem – 70% versus 25%.

Despite growing polarization, leaders from both parties have tried a few times in recent decades to work together on bipartisan reform.

In 2006, former President George W. Bush, a Republican, joined Senators Edward Kennedy, a Democrat, John McCain, a member of the GOP, and other lawmakers in a coalition that pushed for comprehensive immigration reform. Like the 1986 reform, their proposal included stronger border security measures, a path to legalization for undocumented immigrants and a new, expansive program for employers to legally host foreign workers.

Right-wing pundits and anti-immigrant activists vigorously mobilized against the legislation, and the GOP-controlled House of Representatives killed the bill.

In 2013, a bipartisan group of politicians called the “Gang of Eight” spearheaded a new reform. Their bill reflected a familiar package: a new path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants, more work visas for skilled foreign immigrants, and a guest worker program. The Senate passed the legislation, but the measure then died in the House. The Republican majority there refused to vote on what they considered an amnesty bill.

Partisan warfare over immigration reached a fevered pitch during the Donald Trump presidency. Liberals, for example, rallied against Trump’s ban on immigrants from some Muslim countries, and conservatives fretted over caravans of migrants crossing into the country.

3. There’s little bipartisan agreement over what the problem actually is

Most Americans generally agree that the nation’s immigration system is broken. Yet different political groups cannot agree on what exactly is wrong and how to solve it.

For some Republicans, including former Trump, the problem is lax border control and permissive policies that allow dangerous migrants to enter and stay in the country. Right-wing politicians and commentators, like Tucker Carlson, have exploited these anxieties, warning that large-scale immigration will “replace” white Americans. Their solution is to militarize the nation’s borders, deport undocumented immigrants living in the country, and make it harder for people to legally stay in the country.

There are also conservatives who think immigration is consistent with the principles of individual liberty, entrepreneurship and national economic growth. They support more visas for highly skilled newcomers, especially those with strong science and technology backgrounds.

Democrats aligned with the immigrant rights movement believe that the country is obliged to address the humanitarian needs of migrants seeking asylum at the southern border. They argue that millions of undocumented people living in the shadows of American life creates an undemocratic caste system, and they think this can be solved by creating pathways for most undocumented immigrants to get legal permanent residency.

Moderate Democrats advocate tougher restrictions to address migrant surges that overwhelm Border Patrol agents and other officials along the U.S.-Mexican border. Their solutions include hiring thousands of new immigration officers, strengthening physical and technological barriers along the border, and making the asylum program more efficient.

4. Immigration reform is especially messy in a presidential election year

Presidential election years are fertile ground for politicking on immigrants and borders, but not lasting policy reform.

In 2021, President Joe Biden and his supporters introduced an immigration bill that would offer a pathway to legal residency for nearly all undocumented immigrants. But the measure never gained the 60 votes necessary to win passage in the Senate.

Now, Biden finds himself underwater with voters, including Democrats, on immigration and the perceived chaos at the border.

Eager to protect themselves in the 2024 election and to alleviate the headaches that migrant surges at the border present, Biden and other top Democrats temporarily set aside past blueprints for legalizing undocumented people and joined Republican negotiators in advancing one of the toughest border security measures in decades. This bill, which the Senate introduced on Feb. 5, 2024, would have dedicated US$20.2 billion to strengthen border security, and it would have made it much harder for immigrants to apply for or receive asylum.

Republican border hawks had long demanded more restrictive immigration rules. But they did not embrace this deal. When Trump eviscerated the legislation, intent on keeping problems at the border as a campaign issue, Republican members of Congress lined up to quickly kill the legislation.

The death of the bipartisan Senate border deal is a triumph of election-year grandstanding over governing. Yet its demise also reflects a much longer trend of ideological conflict and partisan warfare that has made congressional gridlock on immigration reform a defining feature of contemporary American politics.

Daniel Tichenor does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Source: The Conversation

Shigemi Fukahori, who survived Nagasaki bombing and spent his life advocating for peace, dies at 93

Shigemi Fukahori, who survived Nagasaki bombing and spent his life advocating for peace, dies at 93

South Korean anti-corruption agency asks police to take over efforts to detain impeached Yoon

South Korean anti-corruption agency asks police to take over efforts to detain impeached Yoon

Biden says it is awful that Trump is seeking to do away with US birthright citizenship

Biden says it is awful that Trump is seeking to do away with US birthright citizenship

Zelenskiy says Kyiv security guarantees will only work if US provides them

Zelenskiy says Kyiv security guarantees will only work if US provides them

Biden signs Social Security measure into law to expand benefits for some retirees

Biden signs Social Security measure into law to expand benefits for some retirees

UK business morale hits two-year low after tax rises, survey shows

UK business morale hits two-year low after tax rises, survey shows

China two-year yield eyes fall below 1.00%

China two-year yield eyes fall below 1.00%

Nix leads Broncos past Chiefs' reserves 38-0 and into playoffs for 1st time since 2015 season

Nix leads Broncos past Chiefs' reserves 38-0 and into playoffs for 1st time since 2015 season

Mike McCarthy 'absolutely' wants to return as Cowboys coach, owner Jerry Jones still not definitive

Mike McCarthy 'absolutely' wants to return as Cowboys coach, owner Jerry Jones still not definitive

Buccaneers clinch the NFC South, Commanders lock up the sixth seed and Packers stay at No. 7

Buccaneers clinch the NFC South, Commanders lock up the sixth seed and Packers stay at No. 7

Migrants cross the border from Mexico into Texas on Feb. 6, 2024.

Migrants cross the border from Mexico into Texas on Feb. 6, 2024.