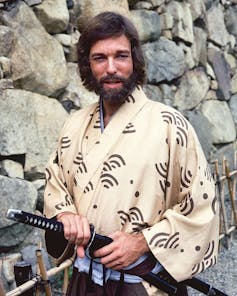

In 1980, when James Clavell’s blockbuster historical novel “Shōgun” was turned into a TV miniseries, some 33% of American households with a television tuned in. It quickly became one of the most viewed miniseries to date, second only to “Roots.”

I’m a historian of Japan who specializes in the history of the Tokugawa, or early modern era – a period from 1603 to 1868, during which the bulk of the action in “Shōgun” takes place. As a first-year graduate student, I sat glued to the television for five nights in September 1980, enthralled that someone cared enough to create a series about the period in Japan’s past that had captured my imagination.

I wasn’t alone. In 1982, historian Henry D. Smith estimated that one-fifth to one-half of students enrolled in university courses about Japan at that time had read the novel and became interested in Japan because of it.

“‘Shōgun,’” he added, “probably conveyed more information about the daily life of Japan to more people than all the combined writings of scholars, journalists, and novelists since the Pacific War.”

Some even credit the series for making sushi trendy in the U.S.

That 1980 miniseries has now been remade as FX’s “Shōgun,” a 10-episode production that is garnering rave reviews – including a near-100% rating from review-aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes.

Both miniseries closely hew to Clavell’s 1975 novel, which is a fictionalized retelling of the story of the first Englishman, Will Adams – the character John Blackthorne in the novel – to set foot in Japan.

And yet there are subtle differences in each series that reveal the zeitgeist of each era, along with America’s shifting attitudes toward Japan.

The ‘Japanese miracle’

The original 1980 series reflects both the confidence of postwar America and its fascination with its resurgent former enemy.

World War II had left Japan devastated economically and psychologically. But by the 1970s and 1980s, the country had come to dominate global markets for consumer electronic, semiconductors and the auto industry. Its gross national product per capita rose spectacularly: from less than US$200 in 1952 to $8,900 in 1980 – the year “Shōgun” appeared on television – to almost $20,000 in 1988, surpassing the United States, West Germany and France.

Many Americans wanted to know the secret to Japan’s head-spinning economic success – the so-called “Japanese miracle.” Could Japan’s history and culture offer clues?

During the 1970s and 1980s, scholars sought to understand the miracle by analyzing not just the Japanese economy but also the country’s various institutions: schools, social policy, corporate culture and policing.

In his 1979 book, “Japan as Number One: Lessons for America,” sociologist Ezra Vogel argued that the U.S. could learn a lot from Japan, whether it was through the country’s long-term economic planning, collaboration between government and industry, investments in education, and quality control of goods and services.

A window into Japan

Clavell’s expansive 1,100-page novel was released in the middle of the Japanese miracle. It sold more than 7 million copies in five years; then the series aired, which prompted the sale of another 2.5 million copies.

In it, Clavell tells the story of Blackthorne, who, shipwrecked off the coast of Japan in 1600, finds the country in a peaceful interlude after an era of civil war. But that peace is about to be shattered by competition among the five regents who have been appointed to ensure the succession of a young heir to their former lord’s position as top military leader.

In the meantime, local leaders don’t know whether to treat Blackthorne and his crew as dangerous pirates or harmless traders. His men end up being imprisoned, but Blackthorne’s knowledge of the world outside of Japan – not to mention his boatload of cannons, muskets and ammunition – save him.

He ends up offering advice and munitions to one of the regents, Lord Yoshi Toranaga, the fictional version of the real-life Tokugawa Ieyasu. With this edge, Toranaga rises to become shogun, the country’s top military leader.

Viewers of the 1980 television series witness Blackthorne slowly learning Japanese and coming to appreciate the value of Japanese culture. For example, at first, he’s resistant to bathing. Since cleanliness is deeply rooted in Japanese culture, his Japanese hosts find his refusal irrational.

Blackthorne’s, and the viewers’, gradual acclimatization to Japanese culture is complete when, late in the series, he is reunited with the crew of his Dutch ship who have been held in captivity. Blackthorne is thoroughly repulsed by their filth and demands a bath to cleanse himself from their contagion.

Blackthorne comes to see Japan as far more civilized than the West. Just like his real-life counterpart, Will Adams, he decides to remain in Japan even after being granted his freedom. He marries a Japanese woman, with whom he has two children, and ends his days on foreign soil.

From fascination to fear

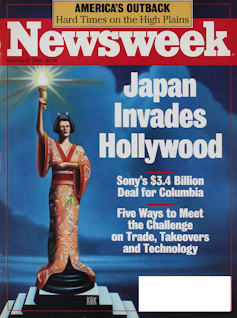

However, the positive views of Japan that its economic miracle generated, and that “Shogun” reinforced, eroded as the U.S. trade deficit with Japan ballooned: from $10 billion in 1981 to $50 billion in 1985.

“Japan bashing” spread in the U.S., and visceral anger exploded when American autoworkers smashed Toyota cars in March 1983 and congressmen shattered a Toshiba boombox with sledgehammers on the Capitol lawn in 1987. That same year, the magazine Foreign Affairs warned of “The Coming U.S.-Japan Crisis.”

This backlash against Japan in the U.S. was also fueled by almost a decade of acquisitions of iconic American companies, such as Firestone, Columbia Pictures and Universal Studios, along with high-profile real estate, such as the iconic Rockefeller Center.

But the notion of Japan as a threat reached a peak in 1989, after which its economy stalled. The 1990s and early 2000s were dubbed Japan’s “lost decade.”

Yet a curiosity and love for Japanese culture persists, thanks, in part, to manga and anime. More Japanese feature films and television series are also making their way to popular streaming services, including the series “Tokyo Girl,” “Midnight Diner” and “Sanctuary.” In December 2023, The Hollywood Reporter announced that Japan was “on the precipice of a content boom.”

Widening the lens

As FX’s remake of “Shōgun” demonstrates, American viewers today apparently don’t need to be slowly introduced to Japanese culture by a European guide.

In the new series, Blackthorne is not even the sole protagonist.

Instead, he shares the spotlight with several Japanese characters, such as Lord Yoshi Toranaga, who no longer serves as a one-dimensional sidekick to Blackthorne, as he did in the original miniseries.

This change is facilitated by the fact that Japanese characters now communicate directly with the audience in Japanese, with English subtitles. In the 1980 miniseries, the Japanese dialogue went untranslated. There were English-speaking Japanese characters in the original, such as Blackthorne’s female translator, Mariko. But they spoke in a highly formalized, unrealistic English.

Along with depicting authentic costumes, combat and gestures, the show’s Japanese characters speak using the native language of the early modern era instead of using the contemporary Japanese that made the 1980 series so unpopular among Japanese viewers. (Imagine a film on the American Revolution featuring George Washington speaking like Jimmy Kimmel.)

Of course, authenticity has its limits. The producers of both television series decided to adhere closely to the original novel. In doing so, they’re perhaps unwittingly reproducing certain stereotypes about Japan.

Most strikingly, there’s the fetishization of death, as several characters have a penchant for violence and sadism, while many others commit ritual suicide, or seppuku.

Part of this may have been simply a function of author Clavell being a self-professed “storyteller, not an historian.” But this may have also reflected his experiences in World War II, when he spent three years in a Japanese prisoner of war camp. Still, as Clavell noted, he came to deeply admire the Japanese.

His novel, as a whole, beautifully conveys this admiration. The two miniseries have, in my view, successfully followed suit, enthralling audiences in each of their times.

Constantine Nomikos Vaporis does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Source: The Conversation

German Christmas market ramming is the latest attack to use vehicles as deadly weapons

German Christmas market ramming is the latest attack to use vehicles as deadly weapons

What we know about the suspect behind the German Christmas market attack

What we know about the suspect behind the German Christmas market attack

How to save a fentanyl victim: Key facts about naloxone

How to save a fentanyl victim: Key facts about naloxone

Pope Francis reprimands Vatican staff for gossiping in annual Christmas message

Pope Francis reprimands Vatican staff for gossiping in annual Christmas message

In a calendar rarity, Hanukkah starts this year on Christmas Day

In a calendar rarity, Hanukkah starts this year on Christmas Day

Russia's UK embassy denounces G7 loans to Ukraine as 'fraudulent scheme'

Russia's UK embassy denounces G7 loans to Ukraine as 'fraudulent scheme'

Drones continue to buzz over US bases. The military isn’t sure why or how to stop them

Drones continue to buzz over US bases. The military isn’t sure why or how to stop them

Senate passes RFK Stadium land bill, giving the Washington Commanders a major off-the-field win

Senate passes RFK Stadium land bill, giving the Washington Commanders a major off-the-field win

Tiger Woods says his son Charlie beat him in a round of golf for the first time, but only on a nine hole course

Tiger Woods says his son Charlie beat him in a round of golf for the first time, but only on a nine hole course

Philadelphia 76ers star Joel Embiid working through injuries and mental health struggles

Philadelphia 76ers star Joel Embiid working through injuries and mental health struggles

Actress Anna Sawai, who plays Mariko in FX's 'Shōgun,' attends the Los Angeles premiere of the series on Feb. 13, 2024.

Actress Anna Sawai, who plays Mariko in FX's 'Shōgun,' attends the Los Angeles premiere of the series on Feb. 13, 2024.