A young Latina mother I was interviewing once laughed uncomfortably as she described her sons’ embarrassment when put on the spot by older Latinos.

They would speak to her sons in Spanish, before quickly adding in the same language, “How awful! You don’t understand me in Spanish?” Her sons would then sheepishly reply – in Spanish – “Yes, I understand. But I don’t speak it.”

Despite our different backgrounds, her story hit close to home.

I grew up in Arizona as the child of Chinese immigrants, learning to navigate the language and cultural currents that surrounded me inside and outside of the home. Reclaiming my Chinese language and understanding its role in my life has been a lifelong journey. At the same time, I was also immersed in the bilingualism of the U.S.-Mexico border, where Spanish and English are both used but the power and politics of language always linger in the background.

I’ve also witnessed these dynamics in my extended family, where my husband’s Latin American roots bring with them the expectation of Spanish fluency. While he is fluent, many children of Latino immigrants are not.

I’ve studied these issues for many years as a linguist, and I’m currently exploring them in my current book project on how language helps shape Latino identity in Washington, D.C.

What I’ve learned upends assumptions that heritage languages are “lost” from one generation to the next because of a simple lack of motivation or children rejecting their roots. My research paints a more complex picture that delves into how we understand – or misunderstand – the bilingualism of heritage speakers.

Assimilation nation

Heritage speakers are people who, although they may have learned their parents’ native language at home, no longer speak it in the same way as a traditional native speaker because of growing up in a bilingual environment.

Their language abilities are often misunderstood both within their cultural communities and by outsiders. That’s what happened with Celia’s sons: Other community members assumed they couldn’t speak Spanish, even though they could understand and respond in the language.

Heritage speakers face a unique set of circumstances. The U.S. has a long history as a multilingual society, and an equally long history of oppressing minority groups and their languages and cultures.

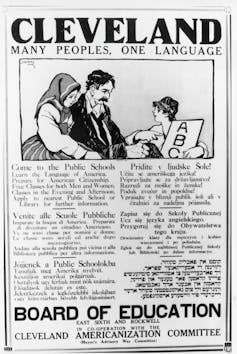

Many U.S. families descended from Europe lost their heritage languages because of pressures to assimilate. Policies promoting English as part of broader “Americanization” efforts were enacted through school policies and legislation in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Most heritage languages in the U.S., such as German and Polish, were no longer spoken in families after three generations.

Meanwhile, Native American groups are still fighting to revitalize languages weakened by targeted cultural eradication. Within living memory, Latinos were punished for speaking Spanish at school. I will never forget when a middle-aged Latina in my bilingual education class shared her humiliation and fear when her kindergarten teacher physically punished her for speaking Spanish – the language of her home and her family, and the only language she spoke at that time. Decades later, the memory was still raw.

Heritage speakers still face discrimination in school, and examples of linguistic prejudice – people being attacked for speaking languages other than English – are rampant on the internet.

Straddling two worlds

Under these circumstances, support for heritage languages in the home and within the community is key. Speaking Spanish is certainly an important value for many Latino parents. But they can be quick to criticize their children’s Spanish acumen, which can inadvertently undermine these efforts.

In my research, I discovered that elders’ negative judgments of the Spanish abilities of younger Latinos created insecurity and language avoidance. Youth were held to unrealistic standards that did not reflect their bilingual realities. When younger Latinos code-switched, understood more than they could say, had a non-native accent in Spanish or spoke English among themselves, older community members often saw this as evidence that they didn’t really speak Spanish.

In reality, these are normal behaviors for the children of immigrants all over the world. But parents’ comparison of their children to monolingual norms – the speech of native speakers who speak only one language – meant that they often inadvertently disparaged their kids’ bilingualism instead of celebrating it.

The relationship between language and identity is intensely personal. Since language is intimately linked to identity, it is often used as a gatekeeper, with young Latinos being shamed for being “Americanized” or seen as rejecting the home culture.

Many of the children and grandchildren of immigrants whom I spoke with told me they felt insecure about their ability to speak Spanish. Even if they were quite fluent, they felt that it was never good enough. As one U.S.-born Latino commented, “I speak Spanish, you know, people down the street can hear me and be like, ‘This guy’s a gringo.’”

Criticizing the way they speak, even with good intentions, can cause them to question their identity and feel insecure, discouraging them from speaking Spanish – the exact opposite of the desired result.

Never enough

While their Spanish comes under attack, Latinos also weather doubts and assumptions about their English. Even Latinos who speak only English get stereotyped as not speaking it based on their ethnicity. People often mistakenly assume that Latino English – a native dialect – is “broken” English, or criticize it as “nonstandard” due to its historic Spanish influence.

Latino English can also experience another layer of prejudice since it is often influenced by African American language, as I found while researching how Latino children acquire their peers’ African American English as a second language.

The heritage-speaker dilemma encapsulates some of the contradictions that Latino youth must navigate: Their parents see them as not Latino enough, while many others view them as not American enough. This dynamic can make them doubt themselves and give others ammunition to question their identities.

These beliefs are so entrenched that even powerful Latinos cannot escape them. U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s bilingualism is constantly under scrutiny. She has been mocked for pronouncing her name in Spanish, as if the English pronunciation were more correct. She’s also been accused of faking her accent.

Criticism of heritage speakers lies in the mistaken belief that there is only one “pure” way to speak a language and that this lines up neatly with culture and identity. But language always evolves, and culture is always changing. Fluid forms, such as Spanglish, play an important role in identity for many young Latinos.

Increasingly, heritage speakers are sharing their experiences and realizing that wherever they are in their language journeys, it’s good enough.

Their language and culture is not “less than” or inauthentic – just different. It’s based on the experience of growing up in a diaspora. Ultimately, many people can identify with their experiences, regardless of their different backgrounds. Learning how to integrate different aspects of yourself into a whole while not losing your roots is a quintessentially American – and, ultimately, human – experience.

Amelia Tseng does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Source: The Conversation

Inflation in Japan's capital accelerates, keeps rate hike prospects intact

Inflation in Japan's capital accelerates, keeps rate hike prospects intact

Brazilian authorities: workers at BYD construction site victims of international human trafficking

Brazilian authorities: workers at BYD construction site victims of international human trafficking

Nidec announces $1.6 billion unsolicited bid for Makino Milling

Nidec announces $1.6 billion unsolicited bid for Makino Milling

Canadian ministers head to Palm Beach for talks with incoming Trump administration

Canadian ministers head to Palm Beach for talks with incoming Trump administration

Why Nefertiti still inspires, 3,300 years after she reigned

Why Nefertiti still inspires, 3,300 years after she reigned

Cole Hutson has 5 assists, defending champion US routs Germany 10-4 in world junior hockey opener

Cole Hutson has 5 assists, defending champion US routs Germany 10-4 in world junior hockey opener

Christmas Eve stowaway caught on Delta airplane at Seattle airport

Christmas Eve stowaway caught on Delta airplane at Seattle airport

Many second- and third-generation Latinos feel insecure about their Spanish-speaking abilities.

Many second- and third-generation Latinos feel insecure about their Spanish-speaking abilities.