In a 1982 video interview, Bernal described his process, and how he would “(work) things out in advance in my head before going out.”

This allowed him to work quickly when he was in someone’s home, minimizing the imposition his presence might cause. He also liked to photograph variations of the same setting – for instance, a room with and without family members, or a scene in both color and black and white. Later, he reviewed all the options, selecting the best from a group of images with subtle differences.

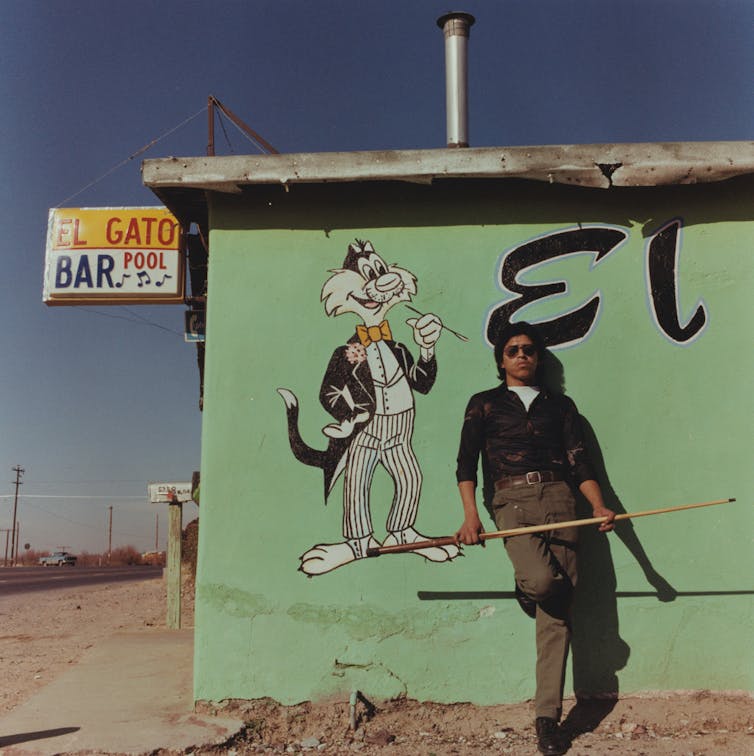

In this way, he was able to create photographs from the world around him based on his deep familiarity with Chicano life and culture. These images introduced a way of life to people beyond the barrios. But they held up a mirror for other Mexican Americans, who could easily recognize the scenes.

“The Chicano artist cannot isolate himself from the community,” Bernal said in 1984, “but finds himself in the midst of his people creating art of and for the people.”

Elevating the everyday

Bernal’s process can be seen in a pair of typical portraits.

In “6th Street Barrio, Douglas, Arizona, 1979,” Bernal photographs a young boy in the living room of his family’s home.

The boy represents one point of a triangular composition. A dark brown, upholstered couch acts as the other, while family photographs high on the yellow wall form the apex. Bernal situated himself across from the corner of the room, where a small end table covered with the family’s possessions sat.

The triangular arrangement of the photograph’s key elements – and the symmetry of the vertical line formed by the room’s corner at center – gives the image balance, stability and permanence, reflecting the way family and home serve as an anchor for the Chicano community.

In “Leon Speer’s Barber Shop, Felix Valdivezo & Daughter Patricia, Lordsburg, New Mexico, 1978,” Bernal places the wall of the barbershop parallel to his lens. This choice creates an organized, composed and easily understood environment in which to make a photograph of the barber, the customer and the customer’s daughter.

Through this perspective – and with some help from a row of mirrors and lights – Bernal captures a little world in its entirety, from the tiled floor reflecting sunlight to the collection of items on a shelf below the pressed-tin ceiling. In doing so, Bernal elevates an ordinary place and everyday people as something special to behold. Instead of the spontaneous and candid qualities you might expect from the casual documentation of, say, a child’s first haircut, Bernal has used a deliberate and formal approach, rendering a familiar subject art-worthy.

Bernal’s legacy

Bernal was building this incredible document of contemporary Mexican American culture when his life was cut short.

He had built the photography program at Pima Community College, in Tucson, Arizona, and his photography practice was thriving. But in 1989, as he was biking to work, he was struck by a car. He spent the next four years in a coma, passing away on his birthday in 1993, at age 52.

Although he had achieved acclaim in the U.S., his career was more acknowledged in Mexico, where he had developed a strong community and thriving professional network. Following his death, his work was not widely circulated in the U.S.

With the establishment of his archive, the publication of “Louis Carlos Bernal: Monografía,” and the opening of a large exhibition celebrating his work, I hope his Chicano pride and artistic vision will be introduced to a new generation of viewers, cementing his legacy in the history of American art.

Rebecca Senf works for the Center for Creative Photography, the non-profit hosting the Louis Carlos Bernal exhibition. The Center for Creative Photography received funding for this project from the Henry Luce Foundation.

Source: The Conversation

Nippon Steel wants to work with Trump administration on US Steel deal, Mori tells WSJ

Nippon Steel wants to work with Trump administration on US Steel deal, Mori tells WSJ

BOJ will raise rates if economy, price conditions continue to improve, Ueda says

BOJ will raise rates if economy, price conditions continue to improve, Ueda says

Stock market today: Asian stocks mixed ahead of US inflation data

Stock market today: Asian stocks mixed ahead of US inflation data

After cable damage, Taiwan to step up surveillance of flag of convenience ships

After cable damage, Taiwan to step up surveillance of flag of convenience ships

As fires ravage Los Angeles, Tiger Woods isn't sure what will happen with Riviera tournament

As fires ravage Los Angeles, Tiger Woods isn't sure what will happen with Riviera tournament

Antetokounmpo gets 50th career triple-double as Bucks win 130-115 to end Kings' 7-game win streak

Antetokounmpo gets 50th career triple-double as Bucks win 130-115 to end Kings' 7-game win streak

Zheng loses to No 97 Siegemund, Osaka rallies to advance at the Australian Open

Zheng loses to No 97 Siegemund, Osaka rallies to advance at the Australian Open

Louis Carlos Bernal, 'Dos Mujeres, Douglas, Arizona,' 1978.

Louis Carlos Bernal, 'Dos Mujeres, Douglas, Arizona,' 1978.