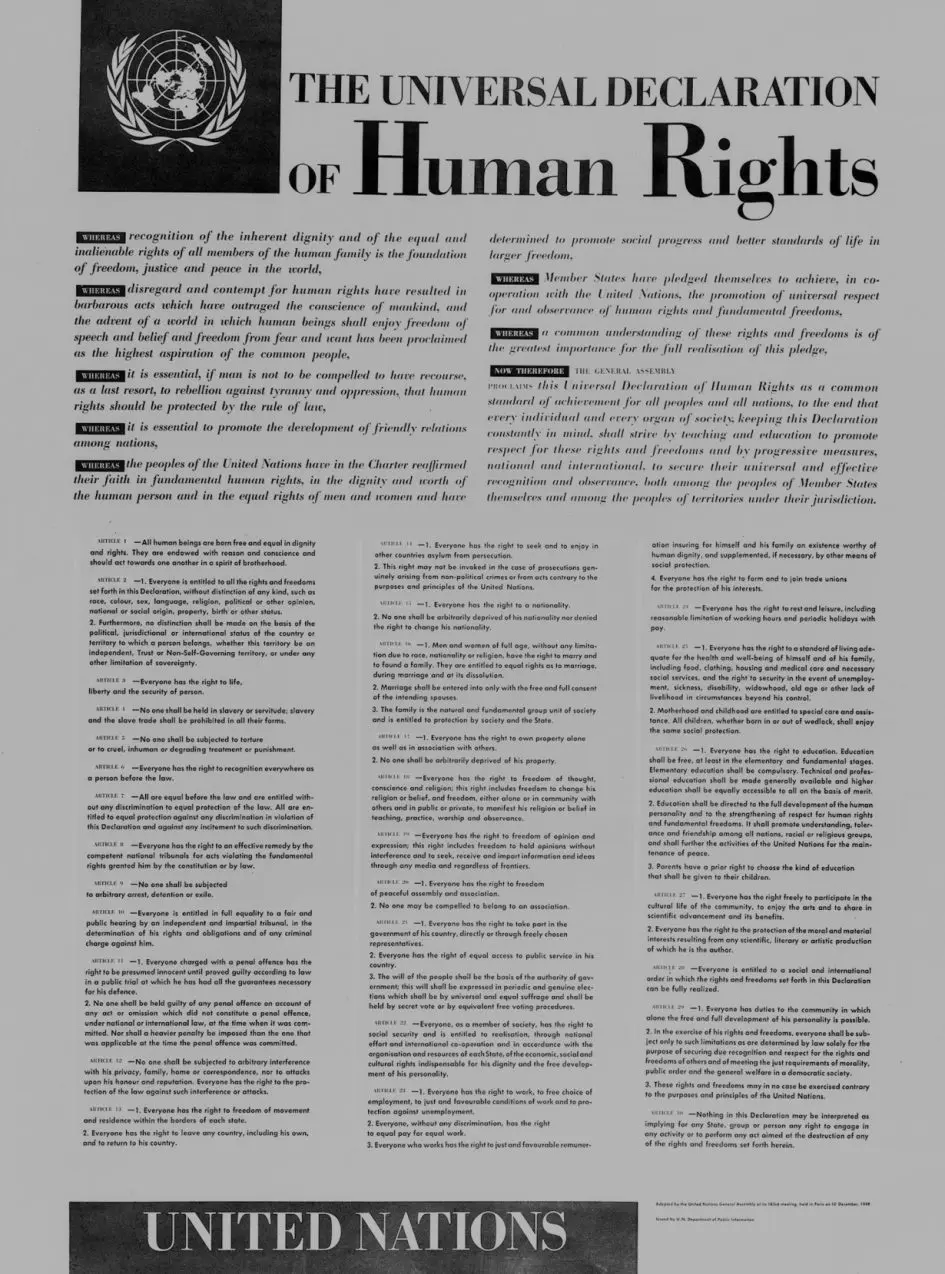

Dec. 10 marks the anniversary of the 1948 signing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations in the aftermath of the Holocaust. Though contested, imperfect and unfulfilled, the declaration remains a milestone in human civilization as one of the earliest times the world came together to distill and assert general principles key to peaceful living on this planet.

Nested in Article 27 of the declaration is a lesser-known right: the human right to science. As a legal scholar, I have immersed myself in the study of this human right for the past six years. This process has allowed me to uncover a multifaceted right containing many entitlements that, together, can reshape the current relationship between science, society and the state.

Even though the international community has paid little attention to this right, and many people may be unfamiliar with it, the human right to science is an important part of the declaration. I believe its dual potential to protect the value of science in society and ensure that science serves humanity is worth discovering and appreciating as a framework to govern scientific progress.

Short history of the human right to science

Article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights reads: “Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.”

The drafters capitalized on the earlier work of the authors of the American Declaration of Human Rights, which had recognized science as a human right just a few months before. In that context, the Chilean delegation argued that culture, the arts and science are crucial forms of human expression deserving the highest recognition.

The transition from the American to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was almost seamless. No opposition was mounted against its inclusion among the human rights. Rather, the debate focused on the legitimacy of governments, under human rights law, to impose political aims on science, an issue that could not be ignored after the U.S. deployment of atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. Ultimately, the view that science should be pursued for the sake of truth and not be tied to any specific purpose prevailed.

The right to science was reaffirmed with the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in 1966 and by the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in 2020.

Science as a cultural right

History is an important guide for the international community as it rediscovers the human right to science. The choice to include science among the cultural rights but distinguish it from other cultural expressions has important consequences for how the human right to science is valued and applied.

By including science among the cultural rights, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights pays tribute to science as an expression of human creativity. As part of culture, science embodies ingeniousness in managing the fragility of the human condition by attempting to know more about it.

The point is well developed in a 2012 report by the then-Special Rapporteur on Cultural Rights Farida Shaheed. There she writes, “The right to participate in cultural life entails ensuring conditions that allow people to reconsider, create and contribute to cultural meanings and manifestations in a continuously developing manner.” The right to science “entails the same possibilities in the field of science, understood as knowledge that is testable and refutable, including revisiting and refuting existing theorems and understandings.”

Science is thus a meaning-making activity that emerges from the scientific community’s concerted effort to deploy human creativity to make sense of the world that people inhabit, including our own selves. This is possible only when human creativity is recognized and guarded. The drafters of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights did not fail to pick up on this cue and included scientific freedom as an element of the human right to science. It asks states to agree to “respect the freedom indispensable for scientific research and creative activity.”

The recognition of scientific freedom as a human right casts science and scientists with a special status in society. They possess the power and responsibility to do good for humanity. These benefits, though, can materialize only if scientific creativity is unleashed and protected.

Science’s unique contribution

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights purposely distinguished “scientific advancement and its benefits” from “the cultural life of the community” and “the arts.” Textual analysis is at the core of legal interpretation, making this choice of words consequential. Parsing cultural rights into three areas – the cultural life, the arts and scientific advancement – and connecting “benefits” to “scientific advancement” signal that what science offers to society is qualitatively different from other forms of culture.

People use a variety of knowledge systems along with science in their daily lives. These include religion, local traditions, indigenous knowledge and superstition. In this mix, science is assigned unique explanatory and practical powers that allow it “to provide the most reliable and inclusive way to understand the universe and the world around and within us.”

The arts uniquely capture universal emotions and can mobilize action, but the artistic experience is inherently subjective and individual. Religion can also organize collective action but is based on conditions of faith rather than trust. By contrast, science stands out as a unique source of shared understanding of what happens in the world around us and inside us. As a collective and concerted attempt to discover truths about the physical and social worlds, science offers reliable insights that can be used as a rational basis for collective action, including policy. Furthermore, science is uniquely positioned to produce benefits for humanity in the form of applied knowledge.

An example of the universal and beneficial character of science is knowledge around cardiac pacing that led to the development of pacemakers to treat arrhythmias. Emerging from the confluence of medicine, biology, physics, chemistry and engineering, the basic and applied knowledge behind pacemakers is universal because the principles used to develop them is consistent across the planet and can be replicated by any lab. Furthermore, the devices are incontrovertibly beneficial to any person suffering from certain heart conditions, irrespective of their creed, identity or nationality.

If you are not persuaded, just think about how the development of eye glasses has improved visual impairment around the world.

Cultivating science for the benefit of humankind

In 1948, the international community agreed to elevate science as a protected human right. The drafters of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights endowed the generations following them with the challenge of using international law to build a better, more peaceful world.

While not a panacea, reaffirming why science is valuable can help improve how it’s practiced and taught, as well as help scientists build trust among the public.

Bringing these principles to life requires the public to support science and demand that it serves humankind. The human right to science gives policymakers and the scientific community the tools to realize this agenda. It is up to everyone to make good use of this gift.

Andrea Boggio does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Source: The Conversation

Police want to talk to man after gun was accidentally fired gun inside Walmart bathroom

Police want to talk to man after gun was accidentally fired gun inside Walmart bathroom

Woman arrested for what was found in 'colorful party bag' during traffic stop, deputies say

Woman arrested for what was found in 'colorful party bag' during traffic stop, deputies say

Device helps police detect drugs safely

Device helps police detect drugs safely

Fact check: Trump makes false claims about trade with Canada and Europe in remarks to Davos

Fact check: Trump makes false claims about trade with Canada and Europe in remarks to Davos

Prince Harry claims court victories. But is he winning the larger war with the British media?

Prince Harry claims court victories. But is he winning the larger war with the British media?

Judge blocks Trump’s ‘blatantly unconstitutional’ executive order that aims to end birthright citizenship

Judge blocks Trump’s ‘blatantly unconstitutional’ executive order that aims to end birthright citizenship

Made in Maine: Kittery company using kelp to help keep skin hydrated

Made in Maine: Kittery company using kelp to help keep skin hydrated

Karla Sofía Gascón makes history with ‘Emilia Pérez’ Oscar nomination

Karla Sofía Gascón makes history with ‘Emilia Pérez’ Oscar nomination

‘Offensive’ tattoos and ‘see-through clothing’ can get you kicked off your next Spirit Airlines flight

‘Offensive’ tattoos and ‘see-through clothing’ can get you kicked off your next Spirit Airlines flight

Ariana Grande pays homage to her ‘Oz’ roots with emotional Oscar nomination reaction

Ariana Grande pays homage to her ‘Oz’ roots with emotional Oscar nomination reaction

There was no opposition to designating science as a human right.

There was no opposition to designating science as a human right.