Top Articles

KROQ DJ Jed 'The Fish' Gould dies at 69

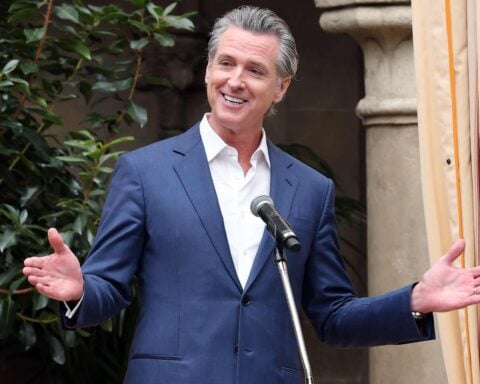

Newsom aims to develop partnerships amid new tariffs

US News

See all »‘The most powerful type of liar’: Tapper asks Anna Delvey how she views her criminal past

Tornadoes, heavy rains rip across central, southern US

Man faces charges after Teslas set on fire with Molotov cocktails

Wisconsin and Florida elections provide early warning signs to Trump and Republicans

World News

See all »Israel to seize parts of Gaza as military operation expands

Middle East latest: Israel is establishing a new military corridor across Gaza

A wary Europe awaits Rubio with NATO's future on the line

China’s military launches live-fire exercise in escalation of blockade drills near Taiwan

Latest

Cory Booker’s historic speech energizes a discouraged Democratic base

Trump's tariffs roil company plans, threatening exports and investment

Businesses around the globe on Thursday faced up to a future of higher prices, trade turmoil and reduced

Stock futures plunge as investors digest Trump’s tariffs

Stock futures plunge as investors digest Trump’s tariffs

Hear Trump break down tariffs on various countries

Attorney for father deported in 'error' says this is what's 'new, unique and terrifying' about case

CNN's Erin Burnett speaks with Simon Sandoval-Moshenberg, the attorney for a Maryland father the Trump administration conceded it mistakenly deported to El Salvador “because of an administrative error.”

Federal judge to consider case of Georgetown fellow arrested by ICE

Federal judge to consider case of Georgetown fellow arrested by ICE

Canadian couple cancels tens of thousands in travel to the US

Europe prepares countermeasures to Trump’s tariffs, calling them a ‘major blow to the world economy’

Europe prepares countermeasures to Trump’s tariffs, calling them a ‘major blow to the world economy’

Exclusive: Secretary of Education explains what department will do after Trump begins dismantling it

Secretary of Education Linda McMahon outlines what she expects the Department of Education will do now following President Donald Trump's executive order that began the process of dismantling the department.

Former federal judge says Trump is playing a 'dangerous game' with Judge Boasberg

Former federal judge John E. Johns III responds to White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller, who said judges have no authority to administer the Executive Branch. Jones also explains why he believes President Donald Trump and his administration are playing a dangerous game by attacking Judge Boasberg.

California & Local

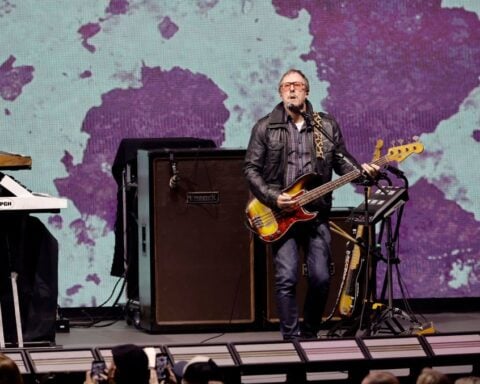

See all »Weezer bassist to play Coachella despite wife’s arrest

KROQ DJ Jed 'The Fish' Gould dies at 69

Technology

See all »Apple CEO spoke with Lutnick about tariff impact on iPhone prices, Washington Post says

Kraken lays off hundreds ahead of IPO, Coindesk reports

What does ruling on Google's illegal ad tech monopoly mean?

Farming couple builds a 'passive house', one of Wisconsin's most eco-friendly and efficient homes

Lifestyle

See all »Farming couple builds a 'passive house', one of Wisconsin's most eco-friendly and efficient homes

NJ pet owner searching for lost dog last seen going under fence into restricted Naval base

Limited-edition Boston Marathon bracelets encouraging egg hunt around city

A restaurant in Havana defies Cuba's tech struggles with digital menus and a robot waitress

Entertainment

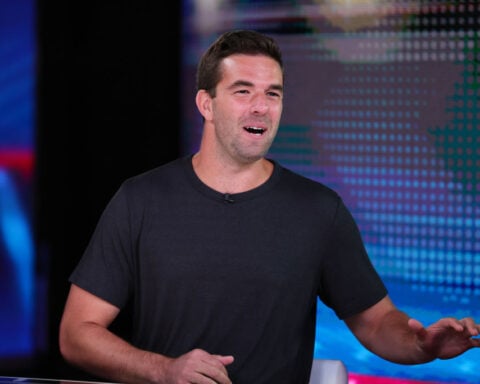

See all »Fyre Festival 2 stops ticket sales for Mexico event

Theater takes action as 'Minecraft Movie' screenings erupt into chaos

Drake complains about Kendrick Lamar's 'Not Like Us' Super Bowl performance in new defamation claims

Dozens more possible jurors are screened in Weinstein retrial

Trump has begun another trade war. Here's a timeline of how we got here

Trump has begun another trade war. Here's a timeline of how we got here

Canada's leader laments lost friendship with US in town that sheltered stranded Americans after 9/11

Canada's leader laments lost friendship with US in town that sheltered stranded Americans after 9/11

Chinese EV giant BYD's fourth-quarter profit leaps 73%

Chinese EV giant BYD's fourth-quarter profit leaps 73%

You're an American in another land? Prepare to talk about the why and how of Trump 2.0

You're an American in another land? Prepare to talk about the why and how of Trump 2.0

Chalk talk: Star power, top teams and No. 5 seeds headline the women's March Madness Sweet 16

Chalk talk: Star power, top teams and No. 5 seeds headline the women's March Madness Sweet 16

Purdue returns to Sweet 16 with 76-62 win over McNeese in March Madness

Purdue returns to Sweet 16 with 76-62 win over McNeese in March Madness