On Thursday, Sept. 20, 1973, singer-songwriter Jim Croce died when his chartered plane crashed shortly after takeoff in Natchitoches, Louisiana. He was 30 years old.

Croce was a chart-topping musician who had performed over 300 concerts in the previous year. He had been in Natchitoches to play that evening at Northwestern State University, making up for a concert canceled the previous spring because he had a sore throat. Croce had performed for an enthusiastic if small audience. Many people had stayed home to watch the televised broadcast of the “Battle of the Sexes” tennis match between Bobby Riggs and Billie Jean King.

In her 2012 book “I Got a Name: The Jim Croce Story,” Croce’s wife, Ingrid, recounted that night: a pilot, Robert Elliott, with a heart condition helming a small Beechcraft E18S; a flight trajectory possibly not accounting for some tall pecan trees; a phone call bearing horrible news.

The crash also killed Croce’s performing partner Maury Muehleisen, comedian George Stevens, manager Kenneth Cortese and tour manager Dennis Rast.

Aircraft crashes have claimed the lives of other popular music acts before and after Croce: Glenn Miller, Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, The Big Bopper, Patsy Cline, Cowboy Copas, Hawkshaw Hawkins, Jim Reeves, Otis Redding, The Bar-Kays, members of Lynyrd Skynyrd, Randy Rhoads, Ricky Nelson, Stevie Ray Vaughan, John Denver and Aaliyah. Croce, like all those musicians, left the world abruptly and far too early, yet his music endured, and fans grew to view him as having achieved a measure of immortality.

From obscure folkie to national star

Croce was an Italian American from Philadelphia and a participant in the 1960s folk music revival. In 1966, he recorded the solo album “Facets,” which revealed to the few people who heard it that Croce was a compelling singing storyteller who could personalize songs composed by others. In 1969, Jim and Ingrid Croce, who toured as a duo, made an album together for Capitol Records. That album, simply titled “Croce,” showcased both Croces as evocative songwriters.

Three years passed. Jim Croce worked various blue-collar jobs to support his family while trying to advance a solo music career. Eventually his management secured a recording deal, and Croce entered a New York City studio, the Hit Factory, to make his third album, “You Don’t Mess Around With Jim.”

The album was released in April 1972 on the ABC label. It featured striking original songs – directly expressed, richly human lyrics matched to pitch-perfect musical structures – all performed by Croce with accompaniment from his new partner, master guitarist and harmony singer Muehleisen. The album yielded three hits: the title track, “Operator (That’s Not the Way it Feels)” and “Time in a Bottle.” The album launched Croce on the national stage as a formidable artist who combined relatability and sincerity with remarkable artistic craftsmanship and an unmistakable voice.

The album “Life and Times,” released in July 1973, sustained Croce’s trajectory, offering original songs that either explored love or celebrated charismatic characters. The album featured his breakthrough hit “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown,” which reached No. 1 on the Billboard singles chart and earned Croce two Grammy Award nominations.

By September 1973, with two albums reaching Gold status for selling 500,000 copies, Croce’s career was soaring. In August and early September 1973, he entered the studio to make new recordings for his next album. That album, “I Got a Name,” was released posthumously on Dec. 1, 1973. It rose to No. 2 on the album chart in 1974 and featured three singles: the title track, “I’ll Have to Say I Love You in a Song” and “Workin’ at the Car Wash Blues.”

“Time in a Bottle” was released as a single posthumously and became Croce’s second No. 1 hit.

A who’s who performing Croce songs

During the 1970s, some music critics accused the singer-songwriter of wallowing in nostalgic sentimentality. This line of criticism, though, didn’t account for such Croce songs as “Next Time, This Time” and “Lover’s Cross” – falling-out-of-love songs as emotionally harrowing as any by other songwriters of that era. Certain Croce songs that did project nostalgia, such as “Walkin’ Back to Georgia” and “Alabama Rain,” inspired generations of country music songwriters.

Fans and fellow musicians did not seem to share the critics’ views of the man and his music. Shortly after his death and for years afterward, Croce was memorialized in popular culture. In 1974, The Righteous Brothers referenced him in a No. 3 single “Rock and Roll Heaven,” while Queen recorded an album track entitled “Bring Back That Leroy Brown.” That same year, The Ventures recorded an album of instrumental interpretations of Croce songs.

Various pop vocalists got into the act. Frank Sinatra, Andy Williams, Bobby Vinton, Lena Horne and Roger Whittaker covered Croce songs. In 1980, Jerry Reed recorded an album of Croce songs, while 1997 saw the release of the album “Jim Croce: A Nashville Tribute.” Over the years, Croce songs have been recorded by country artists including Glen Campbell, Crystal Gayle, Clint Black and Garth Brooks, and by musicians associated with other genres, including Henry Mancini, Shirley Scott, Diana Krall, The Drifters, Babyface and Dale Ann Bradley.

Jim Croce has been commemorated in other ways as well. In 1990, he was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame. In 2022, a Pennsylvania state historical marker was erected at the site of the house where Jim, Ingrid and son A.J. Croce, who became a widely respected singer-songwriter in his own right, lived at the time of his commercial breakthrough.

Ingrid Croce created her own tribute to her former partner, opening a restaurant in San Diego named Croce’s Restaurant and Jazz Club, located on the corner of 5th Avenue and F Street – the site where, in 1973, one week before the fatal plane crash, Jim and Ingrid had talked of establishing a music performance venue. For 30 years, before closing after a lease dispute, the popular restaurant was a place where fans could celebrate Jim Croce and his music.

To honor its namesake, the restaurant hosted live music, and Croce’s gold records were mounted on the wall. Prominently displayed in the restaurant was a rendering of the singer-songwriter, mustachioed and – to quote from his song “Workin’ at the Car Wash Blues” – “smoking on a big cigar.”

Ted Olson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Source: The Conversation

Stabbing attack on woman in Israeli city of Herzliya

Stabbing attack on woman in Israeli city of Herzliya

US equity funds receive big inflows on cool inflation, funding bill, and holiday rally

US equity funds receive big inflows on cool inflation, funding bill, and holiday rally

Suzuki Motor former boss Osamu Suzuki, who turned the minicar maker into a global player, dies at 94

Suzuki Motor former boss Osamu Suzuki, who turned the minicar maker into a global player, dies at 94

German president dissolves parliament for Feb. 23 snap elections

German president dissolves parliament for Feb. 23 snap elections

Ark's Cathie Wood calls for tax clarity as she rides 'Trump bump'

Ark's Cathie Wood calls for tax clarity as she rides 'Trump bump'

Trump's first actions and job data to test market in January

Trump's first actions and job data to test market in January

Father of Raiders star Malcolm Koonce fights to erase 1983 conviction DA says was tainted by police

Father of Raiders star Malcolm Koonce fights to erase 1983 conviction DA says was tainted by police

Azerbaijan Airlines flight to Russia turns back to Baku after airspace closure, TASS says

Azerbaijan Airlines flight to Russia turns back to Baku after airspace closure, TASS says

Jaden Ivey's 4-point play with 3 seconds left rallies Pistons past Kings 114-113

Jaden Ivey's 4-point play with 3 seconds left rallies Pistons past Kings 114-113

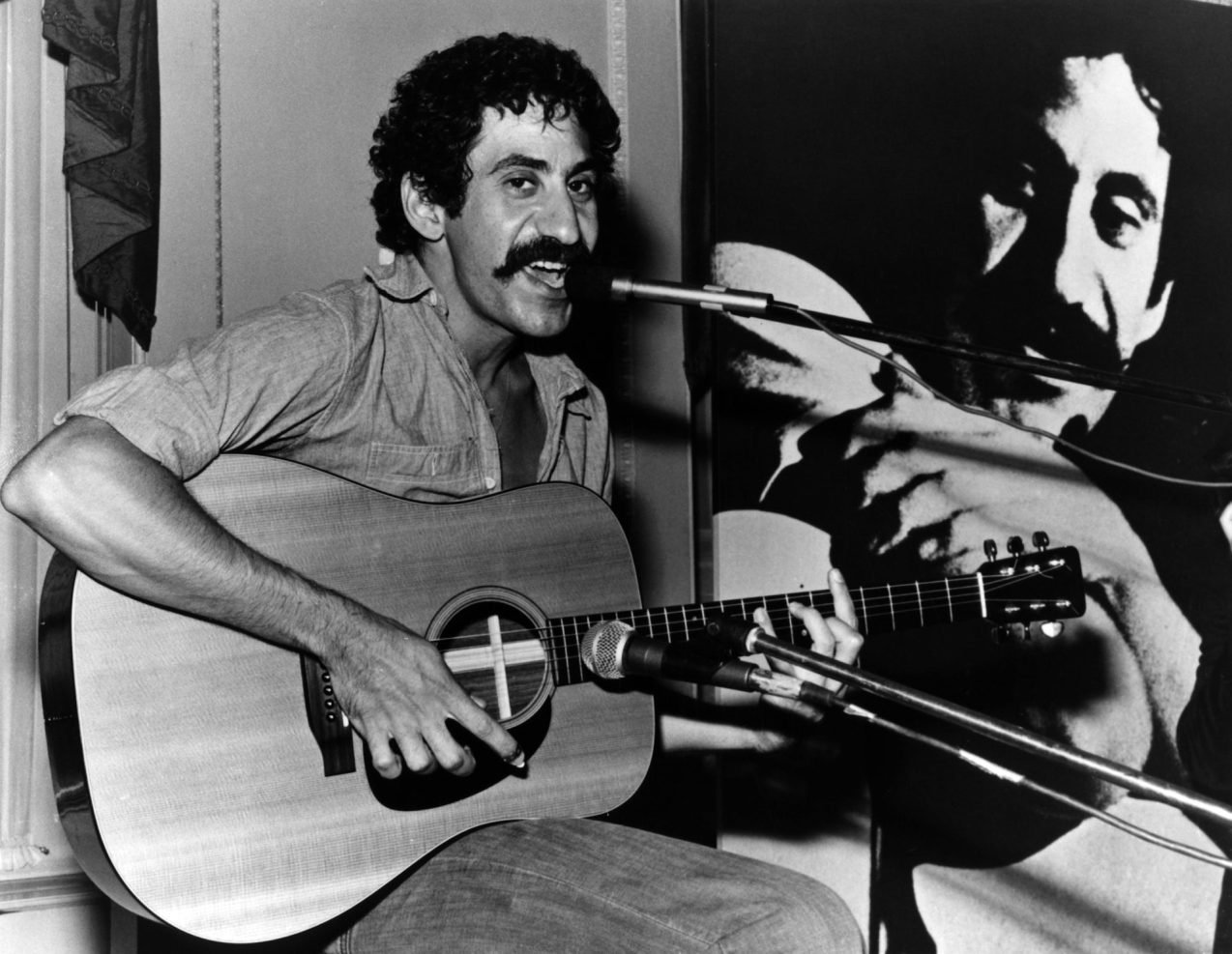

Jim Croce went from struggling folk musician to chart-topping singer-songwriter.

Jim Croce went from struggling folk musician to chart-topping singer-songwriter.