Top Articles

L.A. homeowners sue insurance companies over wildfire coverage

Top beaches to visit in L.A. County this Summer

US News

See all »China vows to counter Trump’s ‘bullying’ tariffs as global trade war escalates

Key takeaways from Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs

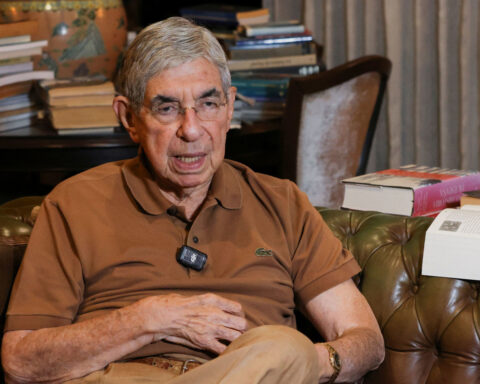

Former Costa Rican president who compared Trump to ‘Roman emperor’ says US has revoked his visa

‘The most powerful type of liar’: Tapper asks Anna Delvey how she views her criminal past

World News

See all »Trump and Zelenskiy meet one-on-one in Vatican basilica to seek Ukraine peace

Former Costa Rican president who compared Trump to ‘Roman emperor’ says US has revoked his visa

The Taliban senses an opening as it pushes for diplomatic recognition in talks with Trump administration

World leaders react to Trump's tariffs

Latest

US Treasury's Bessent urges IMF, World Bank to refocus on core missions

U.S.

Wall Street ends higher on earnings, hopes of easing tariff tensions

U.S. stocks rebounded on Tuesday as a spate of quarterly earnings reports and hints at the de-escalation of U.S.-China trade tensions brought buyers in from the sidelines.

See the moment Vatican announces death of Pope Francis

Former CDC official reveals why he left after RFK Jr. took over

CNN's Anderson Cooper speaks with former CDC communications director Kevin Griffis about his decision to step down after President Donald Trump's pick to lead the agency, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., took over.

Trump said he didn’t sign controversial proclamation. The Federal Register shows one with his signature

President Donald Trump downplayed his involvement in invoking the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to deport Venezuelan migrants, saying for the first time that he hadn’t signed the proclamation, but that he stood by his administration’s move. The proclamation invoking the Alien Enemies Act appears in the Federal Register with Trump’s signature at the bottom. CNN’s Kaitlan Collins reports.

Cory Booker’s historic speech energizes a discouraged Democratic base

Trump's tariffs roil company plans, threatening exports and investment

Businesses around the globe on Thursday faced up to a future of higher prices, trade turmoil and reduced

Stock futures plunge as investors digest Trump’s tariffs

Stock futures plunge as investors digest Trump’s tariffs

Hear Trump break down tariffs on various countries

President Donald Trump announced during a speech at the White House plans for reciprocal tariffs. A group of countries will be charged a tariff at approximately half the rate they charge the United States.

California & Local

See all »Technology

See all »Spain declares state of emergency after nationwide power blackout

Surveillance video shows ATM explosion inside Chinese restaurant in Philadelphia neighborhood

Fighter jet slips off the hangar deck of a US aircraft carrier in the Red Sea, one minor injury

Baltimore man takes plea deal after allegedly framing a former principal with an AI-generated rant

Lifestyle

See all »Surveillance video shows ATM explosion inside Chinese restaurant in Philadelphia neighborhood

Pastor, daycare director arrested on 'human sex trafficking' charge

Meet Savannah's smartest 7-year-old, who wants to join NASA and travel to Saturn's biggest moon

DEA says over 100 undocumented immigrants arrested at "underground nightclub"

Entertainment

See all »Surveillance video shows ATM explosion inside Chinese restaurant in Philadelphia neighborhood

Son stabs father to death with sword before being fatally shot by Florida deputy

Pastor, daycare director arrested on 'human sex trafficking' charge

Baltimore man takes plea deal after allegedly framing a former principal with an AI-generated rant

Trump has begun another trade war. Here's a timeline of how we got here

Trump has begun another trade war. Here's a timeline of how we got here

Canada's leader laments lost friendship with US in town that sheltered stranded Americans after 9/11

Canada's leader laments lost friendship with US in town that sheltered stranded Americans after 9/11

Chinese EV giant BYD's fourth-quarter profit leaps 73%

Chinese EV giant BYD's fourth-quarter profit leaps 73%

You're an American in another land? Prepare to talk about the why and how of Trump 2.0

You're an American in another land? Prepare to talk about the why and how of Trump 2.0

Chalk talk: Star power, top teams and No. 5 seeds headline the women's March Madness Sweet 16

Chalk talk: Star power, top teams and No. 5 seeds headline the women's March Madness Sweet 16

Purdue returns to Sweet 16 with 76-62 win over McNeese in March Madness

Purdue returns to Sweet 16 with 76-62 win over McNeese in March Madness