The Supreme Court has made it more difficult to quote from existing imagery, music and text, and harder to critique society by borrowing and amplifying others’ works.

The 7-2 majority opinion in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith builds on the copyright and fair use decisions of the past 200 years. At first glance, it reads like the triumph of an independent creator over more powerful forces that seek to profit from original work without paying. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, writing for the majority, affirmed the right of photographer Lynn Goldsmith to copyright protection “even against famous artists.”

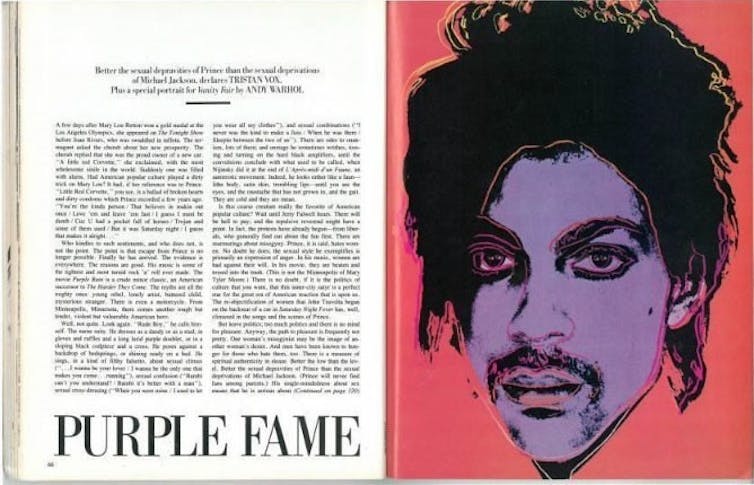

In 1984, Vanity Fair licensed for US$400 a black-and-white photograph of the singer-songwriter Prince, snapped by Goldsmith, to be used by Warhol to illustrate an article about “Purple Rain.” Warhol made colorized, cropped, traced and exaggerated silkscreened versions of the photo.

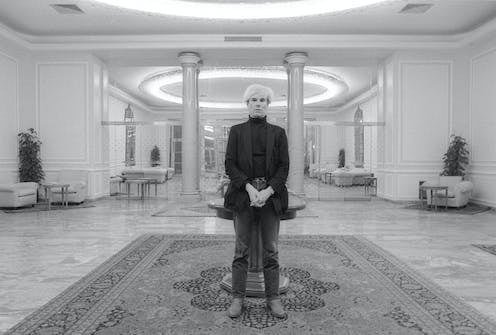

Warhol, a dominant artist from the 1960s on, changed the art scene by incorporating found media – like product labels and celebrity headshots – into silkscreens, often using a repetitive pattern. “Pop art” made everyday images more iconic, while raising questions about how meaning is made.

The Warhol Foundation, Goldsmith claimed, [violated copyright law by distributing] 16 paintings, prints and sketches Warhol made of her photo. These included an orange version that appeared on the cover of Vanity Fair upon Prince’s death in 2016, 12 sold to collectors and galleries, and four sent to the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, where they can be seen for a $25 admission fee.

The majority opinion, finding that the foundation should have included Goldsmith in the deal and sought her permission, will be seen by some as striking a blow for basic fairness in media.

The future of creative freedom

According to the two dissenting justices – Elena Kagan, joined by Chief Justice John Roberts – the majority abandons the law’s historical concern for blocking creativity with demands for permission and payment.

It may now be unlawful to publicize art that imitates other works in some way if the art is intended for a similar outlet, like magazine covers or gallery walls. Narrow exceptions will continue for parody, attacks, history, teaching and minor takings of computer code. But a vast range of expression does not easily fit these exemptions, making it unpredictable to determine whether a new work is legal.

In a much earlier time in American history, copyright law left writers and painters free to decide how to execute a work. Book authors could condense, translate or annotate other authors’ books and be rewarded for their own “learning and judgment” in doing so. Painters could visually quote “the heart” of an earlier painting, meaning the element that gives the painting artistic value.

After the court’s recent decision, reproducing part of a prior author’s work as source material with an expectation of selling or showing the new work for remuneration may be a “showstopper,” to borrow a word Kagan uses in the dissent. Creators may have to pay unpredictable damages or have their work banned outright for failing to seek a license.

All creative work is drawn in some way from the universe of cultural materials that make up its milieu, whether by training the author in the field or developing the genre in which the author works. This fact makes a copyright lawsuit very difficult to defend in court. Under the Warhol decision, commenting on or critiquing another author in the same medium or for a similar audience is nearly incompatible with fair use. Fair use is a flexible doctrine that assesses legality on a case-by-case basis by weighing various qualities of the original and new works.

Stifling artistic studies and YouTube mixes

The implications for contemporary creators are quite serious. Artists frequently imitate other artworks, often acknowledging this with the term “After” in the new work’s title, like Francis Bacon’s Study After Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X. Not only art students but professional artists and those trying to disrupt conventions and forge new paths rely on prior pictures or portraits as materials to be reworked.

Similarly, critics accused philosophers from Plato onward of plagiarism due to their rehashing the theories of other philosophers in new works. With this Warhol decision, this mode of writing will be rather hazardous to release publicly. Why, Plato would be asked at his trial (were he still alive), couldn’t he use words or phrases not already taken by Protagoras?

Musical or cinematic “remix” such as certain YouTube cover songs or SoundCloud mixes will be stifled in many instances. For the past decade, it seemed possible that the Supreme Court would explain that a performer, filmmaker, digital artist or musical producer could legally make a new and jarring contextualization of an audio clip, image or video sequence. The Warhol decision seems to close the door on that idea.

Journalists may also feel the weight of this decision. It is very common for one media outlet to rehash what another has reported. Journalism – and much of what passes for journalism – purports to be factual in nature and will be excluded from copyright protection under the idea-expression dichotomy, which distinguishes creative expression from information, facts and abstract principles. A 1984 decision involving the Nation magazine had already limited this freedom by stating that both direct quotes and paraphrases of factual narratives may weigh against a finding of fair use.

The Supreme Court majority purports simply to be applying the Copyright Act, as revised in 1976. Yet in 1993 and 2021, the court declined to read the act as granting copyright owners control of all economic value emanating from their works even though the Copyright Act gave owners a right to adapt or recast their works into derivative works. The dissent argues that an articulation of a new point of view, a diverse style or an advance in one’s field should be legal as enhancing our culture.

In ruling against the Warhol foundation, Kagan and Roberts point out, the court has effectively deleted portions of the Copyright Act stating that “comment” is often a fair use and that the exclusive right to transform a work is subject to fair use.

A new signal for the algorithm

You can think of the internet as a giant copying machine founded on a mosaic of quotations. While quotation in everyday speech usually refers only to text, as a legal matter, paintings, photographs, computer code and architectural forms are also subject to quotation.

The Warhol ruling sends a message to internet platforms that a creative work deriving value from and in some way competing with a previous work is unlikely to be a fair use, even if its message differs significantly. This “commercialism trumps creativity” approach may result in a diminished ability to report the news, make documentary films, write biographies or even teach a class.

My research deals with how a purely economic approach to copyright and a concomitant disregard for expressive freedoms threaten the digital domain. The ideals of uninhibited public discourse, a universal digital library and fair opportunities to participate in science and culture fall prey to a clearance culture of fines, fees, filters and denied requests for permission.

Many fair use determinations, especially in the future, will be made by software with limited opportunities for human review. Without a clear rule that creators have certain liberties to borrow portions of existing works, new works will be systematically deleted or downranked to oblivion, with little recourse for those who create them.

Despite the dampening effect that the Warhol decision may have, fair use will continue to be with us. Quotation, pastiche, burlesque and mashups are as old as the Book of Genesis.

Hannibal Travis does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Why AP called Arizona for Trump

Why AP called Arizona for Trump

Trump wins Arizona, sweeping all seven battleground states, Edison Research says

Trump wins Arizona, sweeping all seven battleground states, Edison Research says

China, Indonesia enhance ties with key deals on lithium, green energy, tourism

China, Indonesia enhance ties with key deals on lithium, green energy, tourism

Taliban administration officials to attend UN climate conference in Azerbaijan

Taliban administration officials to attend UN climate conference in Azerbaijan

Soldier with Yemen's exiled government opens fire, killing 2 Saudi troops and wounding another

Soldier with Yemen's exiled government opens fire, killing 2 Saudi troops and wounding another

Trump has vowed to kill US offshore wind projects. Will he succeed?

Trump has vowed to kill US offshore wind projects. Will he succeed?

US to speed up interceptor missiles delivery to Ukraine, WSJ reports

US to speed up interceptor missiles delivery to Ukraine, WSJ reports

Jalen Milroe runs wild as No. 11 Alabama thrashes No. 14 LSU 42-13

Jalen Milroe runs wild as No. 11 Alabama thrashes No. 14 LSU 42-13

Justin Allgaier wins 1st NASCAR Xfinity title, capping comeback by passing Hill and Custer late

Justin Allgaier wins 1st NASCAR Xfinity title, capping comeback by passing Hill and Custer late

Evan Mobley scores 23 points and Cavaliers rally past Nets 105-100 to remain perfect at 11-0

Evan Mobley scores 23 points and Cavaliers rally past Nets 105-100 to remain perfect at 11-0