Millions take selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) like Prozac and Celexa to treat depression and anxiety. But for some, once the drugs are stopped, permanent sexual side effects persist, devastating romantic lives.

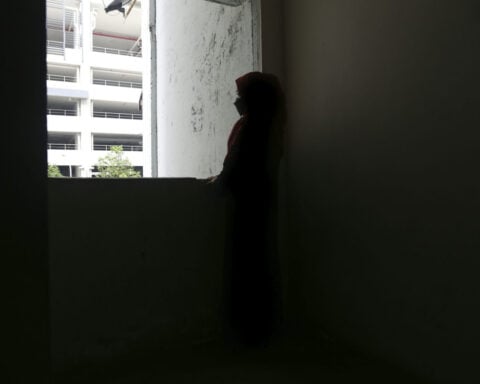

Now a vocal movement is speaking out about post-SSRI sexual dysfunction (PSSD) - a little-known condition where severe sexual problems continue even after quitting the medication. Patients report genital numbness, eliminated libido, and inability to orgasm or feel intimacy.

"My clitoris feels like a knuckle. It's not a normal thing to have to come to terms with," said Emily Grey, who took Celexa at age 17-23 but still suffers symptoms in her late 20s.

While SSRI labels warn sexual issues may continue post-treatment, the chronic dysfunction is contested. "I think it's depression recurring. Until proved otherwise, that's what it is," said psychiatrist Dr. Anita Clayton.

However, specialists in Canada and Europe have recently acknowledged SSRIs can cause lasting sexual impairment. And patient advocates say the drug-induced harm is real.

SSRIs' sexual side effects emerged by the 1990s, so much so the drugs became premature ejaculation treatment. However persistent post-cessation problems garnered little attention until patients began speaking out.

In 2006, reports of enduring genital numbness appeared. “We’ve barely begun to appreciate the complexity of SSRIs’ impact on sexuality,” wrote psychologist Dr. Audrey Bahrick that year in an APA journal. She knew firsthand - Prozac permanently altered her arousal after just one dose.

With SSRI usage skyrocketing, researchers still don't fully grasp the mechanisms. But serotonin blunts sexual response, and SSRIs likely impact hormones like estrogen too.

The effects for some linger after stopping medication. Yet clinical trials rarely monitor post-cessation impacts. "Persistent sexual dysfunction caused by SSRIs is a hypothesis, not proven phenomenon," said researcher Dr. Robert Segraves.

Studies have attempted to quantify PSSD's occurrence. In Israel, 1 in 216 men becoming impotent post-SSRIs was triple the general population's rate. Reports of distinctive, unrelenting genital numbness also signal a potential biological mechanism requiring exploration.

“Everything begins with anecdotal reports, and science needs to follow,” said psychiatrist Dr. Jonathan Alpert. However, vagueness around SSRIs' workings complicates studying PSSD.

Some experts especially worry about youths prescribed SSRIs before their sexuality fully develops. Trans patients also reported higher dysfunction after quitting in a recent survey. "People may never know who they might otherwise be," said counselor Yassie Pirani.

Despite feeling dismissed by doctors who call their symptoms psychological, patients are speaking up. A Reddit group for PSSD suffers has 10,000 members now, up from just 750 in 2020.

In 2018, over 75 patients and doctors petitioned the FDA and European authorities to list PSSD as a side effect. The EU acknowledged the risk in 2019.

“We feel very neglected,” said advocate Roy Whaley, struggling with numbing 16 years post-SSRIs. After years of doctors denying a link, he hopes emerging recognition spurs research.

Counselor Bahrick, who publicized PSSD in 2006 after personal experience, says recognition as the condition spreads is cold comfort given the vast suffering. "It's a reorientation to being in the world," she lamented.

Emerging Recognition of PSSD's Existence

While PSSD was once dismissed as merely continued depression, regulators in Europe and Canada have recently acknowledged SSRIs' potential to cause lasting sexual dysfunction.

This recognition comes after years of patients being told their symptoms were "all in their head," even though histories showed no issues prior to taking SSRIs. Those previously told it was "exceptionally unlikely" their enduring problems were medication-linked finally feel validated.

However, the path toward official medical recognition remains long. Some physicians maintain sexual symptoms after quitting SSRIs are simply depression or conditions like diabetes recurring. They worry warnings could make patients hesitate to try antidepressants.

But specialists counter that clear information allows patients to make informed choices and recognize side effects if they occur. Dismissing patient reports without thorough follow-up stymies science.

As with conditions like fibromyalgia, which many physicians initially brushed off, collective patient voices can push medicine to confront unfamiliar syndromes. Though much work lies ahead, acknowledgment of PSSD represents an important step.

While the medical establishment now shows greater openness to PSSD, research still lags behind anecdotal patient reports. Drug trials rarely follow participants who discontinue medication to quantify enduring effects.

This leaves much unknown about PSSD's prevalence, mechanisms and risk factors. But psychologists say science must catch up with patient experiences instead of dismissing them as anomalies.

Some studies have tracked post-SSRI sexual dysfunction indirectly through metrics like impotence prescriptions in men. More rigorous long-term monitoring of those stopping SSRIs is needed to depict PSSD fully.

Experts stress that suicidality and other serious conditions antidepressants treat remain vitally important to diagnose and medicate. But patients also deserve complete information about potential lasting impacts to make choices aligned with their priorities and values.

Ongoing patient advocacy through groups like RxISK and the PSSD Network has drawn attention from researchers and regulators. Continued efforts combining personal stories and evidence-based data will likely prompt further progress.

While gaps remain around PSSD’s prevalence and causation, one truth is clear: Patients reporting these desperate conditions deserve to be heard, believed, and supported. Their resolve now drives medicine’s evolving understanding.

Trump has begun another trade war. Here's a timeline of how we got here

Trump has begun another trade war. Here's a timeline of how we got here

Canada's leader laments lost friendship with US in town that sheltered stranded Americans after 9/11

Canada's leader laments lost friendship with US in town that sheltered stranded Americans after 9/11

Chinese EV giant BYD's fourth-quarter profit leaps 73%

Chinese EV giant BYD's fourth-quarter profit leaps 73%

You're an American in another land? Prepare to talk about the why and how of Trump 2.0

You're an American in another land? Prepare to talk about the why and how of Trump 2.0

Chalk talk: Star power, top teams and No. 5 seeds headline the women's March Madness Sweet 16

Chalk talk: Star power, top teams and No. 5 seeds headline the women's March Madness Sweet 16

Purdue returns to Sweet 16 with 76-62 win over McNeese in March Madness

Purdue returns to Sweet 16 with 76-62 win over McNeese in March Madness