Experts say scientific research has definitively debunked the long-held belief that yawning occurs when our brains need more oxygen. This revelation comes amid a growing understanding of yawning as a complex physiological mechanism that may serve multiple important functions in human biology.

Research dating back to the 1980s demonstrated that exposure to pure oxygen or high carbon dioxide concentrations had no meaningful impact on yawning frequency. “The brain is still a black box,” said Mark Andrews, chair of physiology at Duquesne University’s College of Osteopathic Medicine, highlighting the continuing mystery surrounding this universal human behavior.

Recent scientific investigations have unveiled several alternative theories about the purpose of yawning. Andrew Gallup, teaching professor of behavioral biology at Johns Hopkins University, notes that yawning often occurs during moments of transition or heightened anticipation. “Yawning also occurs with high frequency during periods in which people are very excited, or there’s a great deal of anticipation,” Gallup said, pointing to observations of Olympic athletes yawning before competition and paratroopers before their first jump.

The physiological impact of yawning extends beyond the familiar jaw-stretching motion. A 2012 study documented increases in heart rate, lung volume, and eye muscle tension during or immediately after a yawn. These physical changes may increase alertness and facilitate state transitions, particularly during sleep-wake cycles.

“It’s part of the stretching of the muscles,” Andrews said. “It starts with the yawn, but there are connections with other muscular activities, so it gets you up and gets you moving.”

One prominent theory suggests that yawning serves as a brain-cooling mechanism. According to research led by Gallup, when brain temperatures rise above baseline levels due to mental exertion, exercise, or emotional states, yawning may help regulate temperature through two primary mechanisms: enhanced blood flow to the brain and heart, and the cooling of blood vessels in the nose and mouth through deep inhalation.

The behavior can occur both spontaneously and through social contagion, with individuals often yawning after seeing, hearing, or even thinking about yawning. Despite its ubiquity, researchers have not reached a consensus on the primary purpose of spontaneous yawning or its exact physiological benefits.

While some people may try to suppress yawns due to social stigma, experts advise against this practice, suggesting that yawning likely serves important biological functions. Alternative behaviors that may achieve similar physiological effects include chewing gum, which research indicates can increase blood flow to the brain, and nasal breathing, which may aid brain temperature regulation. Applying a cold compress to the forehead may also help manage the underlying conditions that trigger yawning.

Starbucks workers expand strike in US cities including New York

Starbucks workers expand strike in US cities including New York

Isolated Chicago communities secure money for a coveted transit project before Trump takes office

Isolated Chicago communities secure money for a coveted transit project before Trump takes office

Caitlin Clark effect hasn't reversed the decades-long decline in girls basketball participation

Caitlin Clark effect hasn't reversed the decades-long decline in girls basketball participation

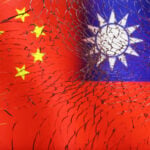

China says US is 'playing with fire' after latest military aid for Taiwan

China says US is 'playing with fire' after latest military aid for Taiwan

Winter is hitting Gaza and many Palestinians have little protection from the cold

Winter is hitting Gaza and many Palestinians have little protection from the cold

China calls Taiwan a 'red line', criticises new US military aid to island

China calls Taiwan a 'red line', criticises new US military aid to island

Trump says he might demand Panama hand over canal

Trump says he might demand Panama hand over canal

Howard throws 2 TD passes to Smith to help Ohio State rout Tennessee 42-17 in CFP

Howard throws 2 TD passes to Smith to help Ohio State rout Tennessee 42-17 in CFP

JuJu Watkins and No. 7 USC hold off Paige Bueckers and fourth-ranked UConn 72-70

JuJu Watkins and No. 7 USC hold off Paige Bueckers and fourth-ranked UConn 72-70