(CNN) — It’s a familiar exchange to many women: “I love your dress.” “Thanks, it has pockets!”

So coveted is the spacious inset pouch in womenswear that when they exist, they are likely to attract attention. Take Dua Lipa’s look at the 2023 Met Gala — a vintage, cream-colored Chanel gown with pockets she was able to slip her hands inside, to the delight of many internet users, or Emma Stone’s decision to stuff the exaggerated hip pockets of her red Louis Vuitton dress with popcorn at Saturday Night Live’s 50th anniversary celebration.

Usable pockets seem like an obvious feature to include in ready-to-wear garments, but that is far from the case. It is standard for dresses and skirts to be pocketless, and when pockets do exist in slacks and blazers, they can be deceptively small. Other times, they’re just deceptive: see the fake pockets that come as a shallow lip over a disappointing seam on a pair of jeans, or a jacket with flaps but no actual opening beneath it.

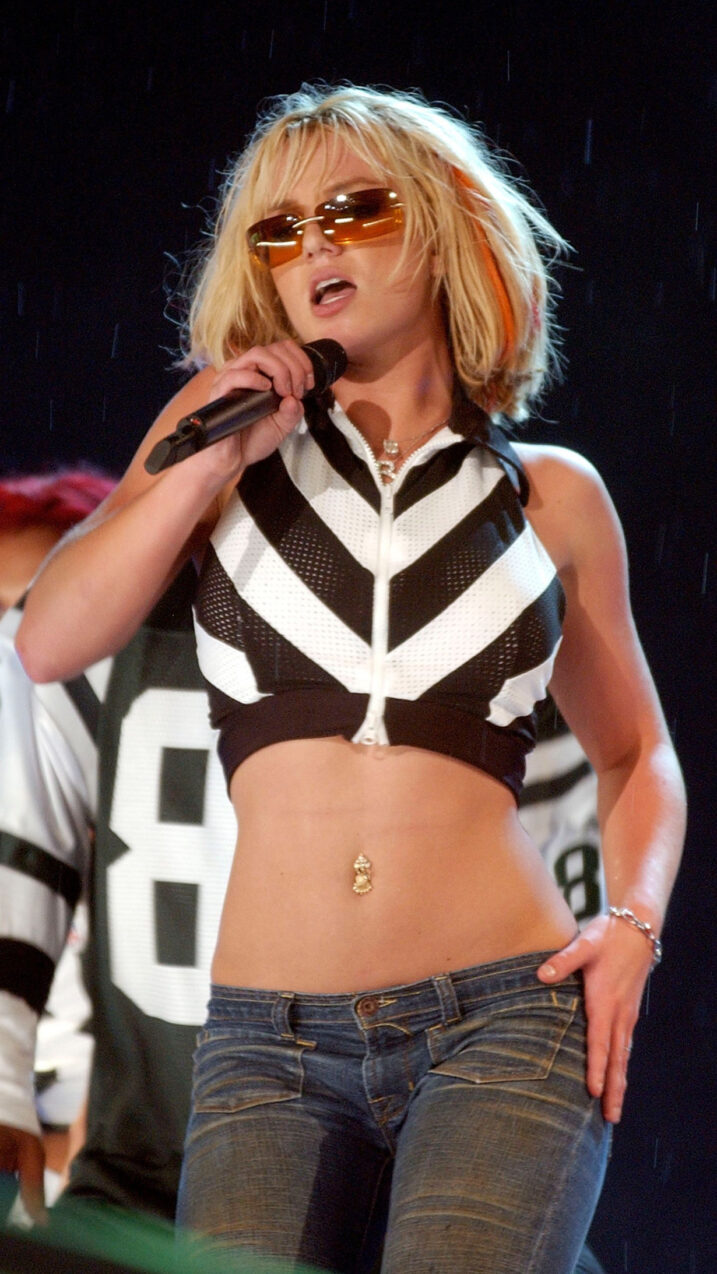

Yet the demand for pockets is clear. Online, fantasies for pocket space find a like-minded audience, from designer Nicole McLaughlin’s hyperfunctional creations made from upcycled materials (chip-and-dip work vest, anyone?) to Y2K throwback creator Erin Miller cramming childhood paraphernalia into her old JNCO jeans, Mary Poppins-style. The question is rinsed and repeated in forums and on social media: Why don’t women get as many pockets as men?

If it all feels vaguely sexist, it is, according to Hannah Carlson, an apparel design lecturer at the Rhode Island School of Design and the author of “Pockets: An Intimate History of How We Keep Things Close.” Since the internal pouch’s arrival in fashion, women have been “differently pocketed,” Carlson said — marking a symbol of gender inequality for hundreds of years.

The lack of pockets in women’s clothing may feel “perplexing,” because they “seem like just this simple, functional device,” she said on a phone call with CNN. “I think objects reveal the things we don’t want to say out loud. We still live in a patriarchy, and (the) objects (in our lives) are made under those conditions.”

A ‘perfect storm’

One of the earliest forms of pockets were drawstring bags stitched into men’s breeches in the 1550s. Before that, both men and women carried their belongings independently. “That men had a fashion bag I think is something we tend to forget,” Carlson explained.

But as tailoring advanced and custom-fit garments were created for men, “pockets really came into play.”

That was largely not the case for women, who at the time continued to wear purses suspended from their belts. As menswear evolved it began to incorporate a variety of pockets, evident in the European three-piece suits developed from Persian kaftans by the late 17th-century, she noted.

Carlson found that it took centuries for womens’ clothing to acquire practical pockets at all. Instead, they were saddled with awkward options, including tear-shaped pouches stitched onto skirts or tie-on pockets that were always at risk of coming undone. For a brief period in the 1870s and ’80s, dressmakers placed pockets in the back of the bustle, requiring wearers to slip a hand backwards and rummage around for their belongings. When some French and British female equestrians adopted riding overcoats with pockets during the 18th century, they were nicknamed “Amazons” — after the female warriors in Greek mythology — and criticized for their masculine dress.

Pockets had become associated with an adventurous, enterprising (and therefore, male) spirit, as evidenced by the tools and objects scaled down to fit inside them: the pocket knife, pocket watch and pocket pistol, to name a few. Carrying a number of objects on oneself was considered resourceful, according to Carlson — but not for women, whose tie-on pockets, popular across the 17th and 18th centuries, were likened to female genitalia by caricaturists or ridiculed in writings from the era, with their size equaling suspicion for what was inside.

Transporting too many belongings had negative implications of gender and class, not unlike the “ludicrously capacious bag” in the final season of TV series “Succession.’” The remark was made by the calculating corporate climber Tom Wambsgans, on spotting a large Burberry handbag worn by a woman outside of the Roy family’s inner circle. (“What’s even in there?” Wambsgans speculated. “Flat shoes for the subway? Her lunch pail? It’s gargantuan. You could take it camping. You could slide it across the floor after a bank job.”)

Pockets prompted a range of connotations for men who kept their hands inside them — criminal activity, sexual deviancy, rebellious attitudes — further reinforcing them as a distinctly male feature. But at their core, pockets represented functional clothing, and women’s dress was meant to be decorative; these ideas crystallized during the Enlightenment era, which also led to men ditching their heels and more ornate adornments, and instead adopting more sober, standardized dress.

“Men’s fashion was systematized a century earlier than women’s,” Carlson pointed out. With no tradition for women’s pockets, they were left out; instead handbags emerged as an entire market for holding women’s things.

“It’s historical circumstance and contingency and sexism all together, it’s like this perfect storm,” she said.

Utility versus fit

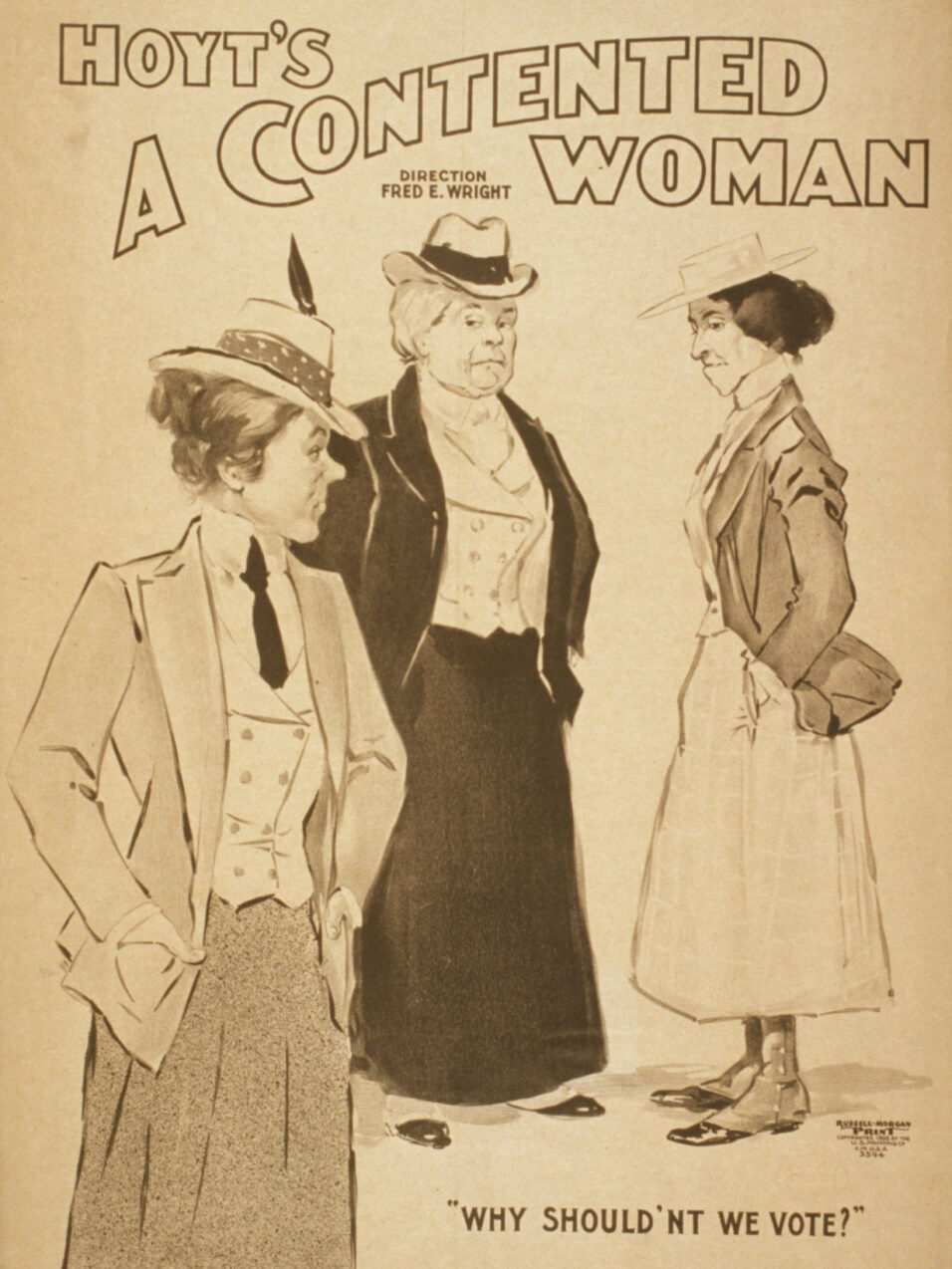

Today’s disgruntled calls for pockets are not new — in fact they became associated with the Suffrage movement at the turn of the 20th century as women demanded the right to vote. Men walked down the street “free as a lark,” activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton once complained, according to “Pockets,” while women were restricted by holding or carrying their belongings. Retorting against the anti-Suffragist idea that voting was not a “natural right” for women, feminist poet Alice Duer Miller used the right to pockets as a biting metaphor in the 1915 publication, “Are Women People? A Book of Rhymes for Suffrage Time.”

But as womenswear modernized in the 20th century across the West, allowing wearers to ditch restrictive corsets and full skirts and opt for a wider range of silhouettes, pockets finally made more regular appearances. Wartime accelerated these changes, with more women requiring practical outfits — which included pockets — as they entered the workforce and enlisted in the military.

In the pages of Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, fashion illustrations imagined new feminine takes on the component: snap pockets and coin-purse-style pockets on outerwear, or pockets tailored to the needs of computer programmers (designed by Bonnie Cashin and illustrated by Andy Warhol in 1958) or to hold tennis balls on the courts. In 1940, the transformative fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli designed a gold-embroidered dinner jacket with “cash and carry” front pockets to replace the handbag — and in case the wearer needed her hands free to secure her gas mask.

Still, the sexist double standards around pockets have continued to be present in absurd ways. In World War II, the 150,000 volunteers for Women’s Army Corps (WAC), who served in non-combat roles, carried regulation leather purses as part of their uniforms, which included faux pocket flaps. “Army designers cannot figure out how to make a useful pocket for women; they get rid of the breast pocket, because it’s unseemly to put your hand in your breast,” Carlson explained. Because the organization was met with derision by the press and public, “the uniform had to be as feminine as possible.”

Postwar, and with the efforts of second-wave feminism in the 1960s, pants became more widely acceptable for women, but pocket sizes have not always followed. A 2018 study by online culture publication The Pudding comparing men’s and women’s skinny jeans and straight jeans found striking disparities in size, with women’s designs often unable to hold basic personal items or the wearer’s hand.

The acceleration of fast fashion has only complicated the issue, as non-essential features are cheapened or ditched in a bid to push down prices. By now, the idea is firmly entrenched: pockets are a given for men’s clothing, but expendable for women’s.

The fashion industry “assumes women are going to carry handbags and doesn’t want to (put in) the extra work and cost,” Carlson said.

Pockets continue to be seen as an interruption, too, as designers have emphasized clothing that elevates the contours of women’s bodies at the expense of carrying space. That’s not to say that pockets never get a moment — cargo pants are back (though some, inexplicably, have pockets without buttons) and fashion designers have been praised for bringing the pocket back on the runway. But their historic lack of availability makes them something to be noted and noticed, a space to hold objects of desire that has become one itself.

Ultimately, the idea that “fit is more important than utility” has remained, Carlson said. That even goes for “utilitarian” styles — this writer’s ASOS jumpsuit, worn while reporting this piece, has three fake pocket flaps on the chest and in the back. There may be larger concerns for women’s rights in any given decade, but the pocket remains a small, glaring reminder of gender inequality, and is, frankly, a nuisance.

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2025 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.

Trump has begun another trade war. Here's a timeline of how we got here

Trump has begun another trade war. Here's a timeline of how we got here

Canada's leader laments lost friendship with US in town that sheltered stranded Americans after 9/11

Canada's leader laments lost friendship with US in town that sheltered stranded Americans after 9/11

Chinese EV giant BYD's fourth-quarter profit leaps 73%

Chinese EV giant BYD's fourth-quarter profit leaps 73%

You're an American in another land? Prepare to talk about the why and how of Trump 2.0

You're an American in another land? Prepare to talk about the why and how of Trump 2.0

Chalk talk: Star power, top teams and No. 5 seeds headline the women's March Madness Sweet 16

Chalk talk: Star power, top teams and No. 5 seeds headline the women's March Madness Sweet 16

Purdue returns to Sweet 16 with 76-62 win over McNeese in March Madness

Purdue returns to Sweet 16 with 76-62 win over McNeese in March Madness