On a litter-strewn L.A. Street, dozens of people line up. Some are behaving erratically, some stare at the ground ahead of them. Some smoke crack cocaine or inject drugs on the sidewalk. They are waiting at a non-profit to receive clean needles and pipes, as well as coffee and access to a laundry and shower. This is a lifeline for many. One person leaves a review, saying “Sometimes a warm cup of coffee and something warm to eat is the difference between life and death these people are saints all of them” [sic]. But nearby residents may not share the same feelings, and concerns about safety and cleanliness are constantly raised.

The non-profit, Homeless Healthcare Los Angeles, takes an approach to drug use known as ‘Harm Reduction.’ According to Eric Single of the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, the term can be defined as the effort to “ameliorate adverse consequences of drug use while, at least in the short term, drug use continues.” Essentially, they provide needles and pipes in order to reduce the spread of infectious diseases, while not specifically tying their aid to users’ attempts to quit.

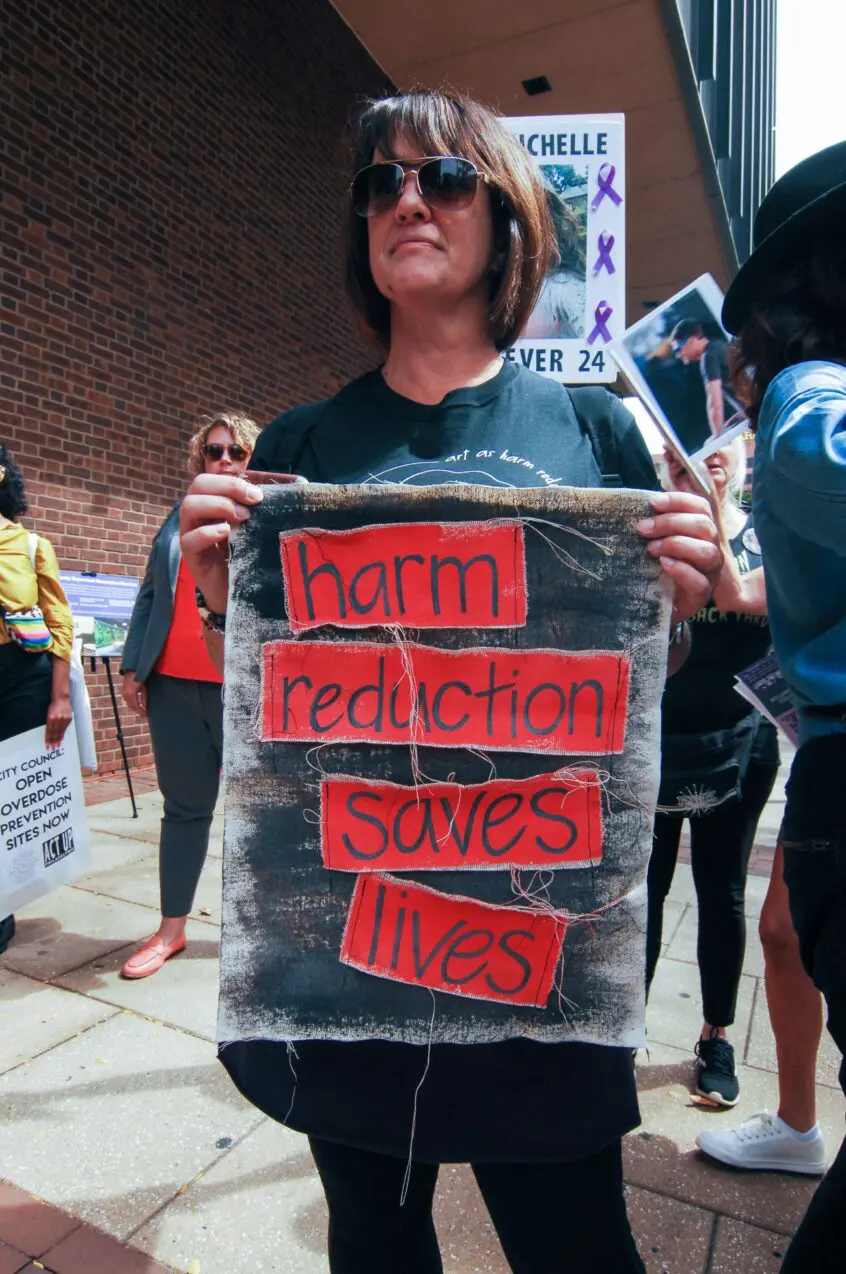

The number of American Syringe Services Programs (SSPs), a key type of harm reduction center, has grown from 33 in the early 90s to over 300 in 2018. While the idea has broad support amongst experts in the treatment of substance abuse, critics allege that it may amount to the enablement of drug use. Reporters and politicians have accused city governments of running “crack-houses” and “drug dens,” and communities across the state are banning the practice.

But is this a fair characterization? The results of these programs, when they can be studied and quantified, are often quite positive. This is true even when looking at their effects on overall drug use. We talked to several experts to find out what readers should consider when they see headlines about these programs.

What is Harm Reduction?

The one thing that sets harm-reduction policies apart from elimination-based ones is that the former do not aim to get users to immediately stop the practices that they are being treated for. Instead, they attempt to alleviate their worst effects. For example, elimination-based sexual education programs teach that abstinence is the best way to stay healthy, whereas those oriented towards harm reduction stress the importance of contraception, testing, and preventative care.

When it comes to drug use, practices labeled as ‘harm reduction’ can vary widely in how close they put the provider to the illegal substances. At the more restrained end of the spectrum are familiar measures such as awareness campaigns and the distribution of Methadone (a drug that helps to ease withdrawals from opiates). Counseling can also help current users reduce their intake or stop altogether.

Some more ambitious initiatives provide users with the means to consume drugs in a safer manner. Syringe Services Programs (SSPs) hand out clean needles in order to stop the spread of infectious diseases among users; supervised injection sites allow people to use drugs in the presence of medical professionals in order to avoid fatal overdoses; and safer supply programs give users access pharmaceutical-grade narcotics in place of risky street-sourced drugs.

Currently in California there are only a limited number of active harm-reduction interventions. The state does not have a supervised injection site, where users may inject narcotics in the presence of medical professionals. Nor is there a safer supply program within the state’s boundaries. A number of organizations provide clean needles and pipes, as well as items like Naloxone, which can reverse opiate overdoses.

What is the Controversy?

The most obvious objection to the practice of harm reduction may be that it could encourage drug use, or else appear as an endorsement of risky practices on the part of the institution providing the service. For instance, when safer supply programs offer regulated narcotics to users, they are in effect giving out intoxicants.

Some former addicts say that easy access to paraphernalia can make it difficult to quit. “If they had been doing this while I was homeless and living there, I would never have left. I would have died in the street,” Michael Ramirez, a former addict, told the California Globe.

But advocates point out that drug users who use needle exchanges have significantly better chances of quitting substances entirely. “Those who come to syringe service programs are five times more likely to go into treatment and and a half times more likely to stop injecting,” says Dr. Beth Meyerson, director of the Harm Reduction Research Lab at the University of Arizona College of Medicine

She attributes this effect to the way that nonjudgmental programs can engage drug users with other support services. “These programs actually create a trust bridge with other support services,” says Meyerson. “If I am maligned from the health system because I’m worried about being arrested or I’m what the community deems ‘illegal,’ I’m not accessing health care any time soon, but the syringe service program that I have a trusted relationship with actually might link me to a really cool mobile health unit.”

Another objection is that harm-reduction facilities may concentrate drug users around their premises. While people injecting on the street may not be a severe problem in isolation potentially-dangerous behaviors have been reported in areas around needle exchanges. Estela Lopez, director of the Los Angeles Downtown Industrial Business Improvement District, has recently received a number of complaints alleging that a program aimed at providing clean paraphernalia to drug users has been causing chaos in the surrounding community. “I started getting feedback from some of our business stakeholders a couple of years ago that things were kind of getting a little off the rails outside of the center, that there were fights and drug sales and drug use outside the center,” she told the Los Angeles Post. “The business that was right next door to them left. They just said, ‘We can’t handle this. None of our customers want to come here.’ They broke their lease and got out.”

Still, others with experience running centers disagree that they are the cause of these problems. Laura Guzman, Executive Director of the National Harm Reduction Coalition, disputes the idea. “I actually managed a drop-in center for sixteen years in the Mission District, and we were told over and over that we were driving homeless people into the neighborhood." She says that, because her center included a shelter and links to other resources, it functioned overall to move people off the street and into housing. “People got services: they got a roof where they could actually get respite for twelve hours a day. They got access to a clinic — we had behavioral health, we had showers.”

Lopez maintains that the problems around the clinic are much worse while it is operating than while it is closed. “When they open their doors, that’s when the mayhem starts. And then when they close for the day, it decompresses on its own.” However, she concedes that she is only looking at immediate effects. Lopez says that she is not commenting on harm reduction approaches in general, and does not know whether they are effective at reducing crime or mortality in the long-term.

What Does the Evidence Tell Us?

There is evidence that specific programs, such as needle exchanges, can reduce overdose deaths and the transmission of infectious diseases. Dr. Meyerson points to a large meta-analysis which shows a 50% reduction in the incidence of HIV and Hepatitis C.

A paper on British Columbia’s safer supply policies found that it reduced overdose deaths by 55% in the week after services were dispensed. A separate study on the same policy found an increase in hospitalizations. Given that only 5% of opioid users in the province had access to safer supply, the authors of this later study have warned readers not to take it as evidence that harm reduction does not work.

There are other benefits to both drug users and the surrounding communities. Dr. Meyerson points to the case of Austin, Indiana, where “235 people… were infected with HIV as a result of this outbreak [among drug users].” A study modeling the potential effects of decriminalized syringe access, along with the other interventions which were eventually implemented, found that if the county had acted earlier, it “would have seen a reduction of 173 cases of HIV. Only 62 people would have been infected, and… every man, woman, and child in that county would have been saved over $3,000,” according to Dr. Meyerson.

Still, she indicates that studies on harm-reduction as a whole are not as conclusive. She points to a large study in the New England Journal of Medicine which examined the results of hundreds of community-selected interventions. The paper did not find any significant differences as a result of the implementation of harm-reduction policies, Meyerson attributes this outcome in part to differences in implementation across communities. The study, which took place in 2021 and 2022 during the COVID-19 Pandemic, involved over six hundred different interventions. “It’s highly possible that these communities selected these interventions and actually implemented them differently,” says Dr. Meyerson.

Conclusion

While we don’t know everything about the effects of harm reduction centers, much critical media coverage exaggerates their drawbacks. Evidence about the potential harms of such centers tends to be anecdotal or inconclusive, while we have robust findings about their benefits. And even those who do not use illegal drugs can benefit from lower disease rates and lower costs to local governments.

Questions about the ethics of providing paraphernalia may remain. However, it is clear that the most common harm reduction initiatives do not encourage drug use. In fact, the opposite may be true. Because they can link users to other services, they can help them to control and reduce their drug use in the long term.

Critics sometimes blame harm-reduction clinics and other forgiving drug policies for America’s increasing overdose rate. But this misses how few of these efforts there actually are in this country. Australia, with a population a third smaller than that of California, has over 4,000 needle exchanges compared to California’s eighty-five. Meanwhile, people overdose there at less than a quarter of the rate at which they do here. Harm-reduction in America is still new and relatively marginal; our problems with opiates and stimulants started long before it was introduced.

Despite this, popular pressure has been successful in shutting down needle exchanges, such as the one in Santa Ana. The L.A. Times recently noted a wave of communities banning the centers across the state. The problem, as seen on L.A.’s Skid Row, is that they can concentrate behaviors — which might be considered unsightly — in specific locations. But studies have not found increases in actual crimes.

Ultimately, it is the responsibility of politicians and voters to decide between short-term cosmetic improvements and long-term control of drug safety. Harm reduction approaches are valuable, even necessary tools, but are limited in their effectiveness by bad optics and disingenuous reporting. At a time when sensationalized content often spreads faster than reliable information, the challenge is to carry out the most effective policies, while keeping our communities on board.

Woman grateful to make it to work safely after passing deputy-involved shooting

Woman grateful to make it to work safely after passing deputy-involved shooting

What is DeepSeek, the Chinese AI company upending the stock market?

What is DeepSeek, the Chinese AI company upending the stock market?

Driver and passenger dead after car crash ignites gas line

Driver and passenger dead after car crash ignites gas line

Gazans already enduring health issues, lack of clean water now face hazardous rubble

Gazans already enduring health issues, lack of clean water now face hazardous rubble

Israel's far-right finance minister withdraws threat to quit coalition over ceasefire deal

Israel's far-right finance minister withdraws threat to quit coalition over ceasefire deal

Former Archegos CFO Halligan gets 8-year prison sentence

Former Archegos CFO Halligan gets 8-year prison sentence

Stella McCartney label leaves LVMH, designer remains sustainability ambassador

Stella McCartney label leaves LVMH, designer remains sustainability ambassador

Orioles hire former All-Star outfielder Adam Jones as special advisor to GM and community ambassador

Orioles hire former All-Star outfielder Adam Jones as special advisor to GM and community ambassador

Beyoncé, Kendrick, Sabrina and more: AP writers predict who will win at the 2025 Grammys

Beyoncé, Kendrick, Sabrina and more: AP writers predict who will win at the 2025 Grammys

The non-profit, Homeless Healthcare Los Angeles, takes an approach to drug use known as ‘Harm Reduction.’

The non-profit, Homeless Healthcare Los Angeles, takes an approach to drug use known as ‘Harm Reduction.’